Wiretap Report 2001

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

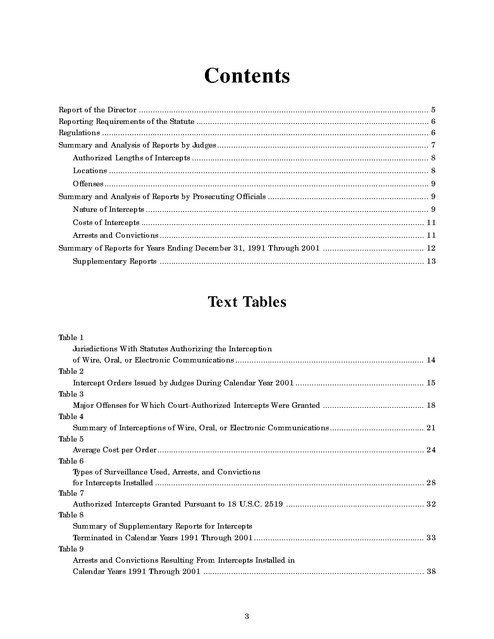

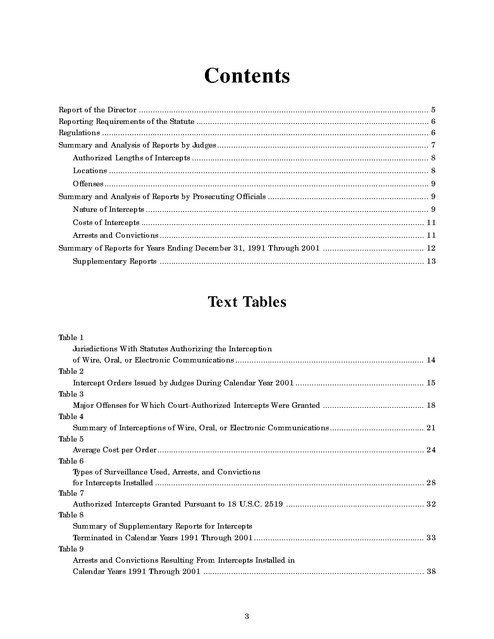

Contents Report of the Director .............................................................................................................................. 5 Reporting Requirements of the Statute ..................................................................................................... 6 Regulations .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Summary and Analysis of Reports by Judges ............................................................................................ 7 Authorized Lengths of Intercepts ....................................................................................................... 8 Locations ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Offenses ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Summary and Analysis of Reports by Prosecuting Officials ...................................................................... 9 Nature of Intercepts ........................................................................................................................... 9 Costs of Intercepts ........................................................................................................................... 11 Arrests and Convictions ................................................................................................................... 11 Summary of Reports for Years Ending December 31, 1991 Through 2001 ............................................ 12 Supplementary Reports ................................................................................................................... 13 Text Tables Table 1 Jurisdictions With Statutes Authorizing the Interception of Wire, Oral, or Electronic Communications .................................................................................. 14 Table 2 Intercept Orders Issued by Judges During Calendar Year 2001 ........................................................ 15 Table 3 Major Offenses for Which Court-Authorized Intercepts Were Granted ............................................ 18 Table 4 Summary of Interceptions of Wire, Oral, or Electronic Communications......................................... 21 Table 5 Average Cost per Order.................................................................................................................... 24 Table 6 Types of Surveillance Used, Arrests, and Convictions for Intercepts Installed ..................................................................................................................... 28 Table 7 Authorized Intercepts Granted Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 2519 ............................................................ 32 Table 8 Summary of Supplementary Reports for Intercepts Terminated in Calendar Years 1991 Through 2001 .......................................................................... 33 Table 9 Arrests and Convictions Resulting From Intercepts Installed in Calendar Years 1991 Through 2001 ................................................................................................ 38 3 Appendix Tables Table A-1: United States District Courts Report by Judges ............................................................................................................................. 40 Table A-2: United States District Courts Supplementary Report by Prosecutors ............................................................................................. 84 Table B-1: State Courts Report by Judges ........................................................................................................................... 108 Table B-2: State Courts Supplementary Report by Prosecutors ........................................................................................... 216 4 Report of the Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts on Applications for Orders Authorizing or Approving the Interception of Wire, Oral, or Electronic Communications The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 requires the Administrative Office of the United States Courts (AO) to report to Congress the number and nature of federal and state applications for orders authorizing or approving the interception of wire, oral, or electronic communications. The statute requires that specific information be provided to the AO, including the offense(s) under investigation, the location of the intercept, the cost of the surveillance, and the number of arrests, trials, and convictions that directly result from the surveillance. This report covers intercepts concluded between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2001, and provides supplementary information on arrests and convictions resulting from intercepts concluded in prior years. A total of 1,491 intercepts authorized by federal and state courts were completed in 2001, an increase of 25 percent compared to the number terminated in 2000. In 2001, wiretaps installed were in operation on average 9 percent fewer days per wiretap than in 2000, and the number of intercepts per order was 12 percent lower. The average number of persons whose communications were intercepted declined 56 percent, from 196 per wiretap order in 2000 to 86 per order in 2001. Public Law 197, 106th Cong., amended 18 U.S.C. 2519(2)(b) to require that reporting should reflect the number of wiretap applications granted for which encryption was encountered and whether such encryption prevented law enforcement officials from obtaining the plain text of communications intercepted pursuant to the court orders. Encryption was reported to have been encountered in 16 wiretaps terminated in 2001; however, in none of these cases was encryption reported to have prevented law enforcement officials from obtaining the plain text of communications intercepted. The appendix tables of this report list all intercepts reported by judges and prosecuting officials for 2001. Appendix Table A-1 shows reports filed by federal judges and federal prosecuting officials. Appendix Table B-1 presents the same information for state judges and state prosecuting officials. Appendix Tables A2 and B-2 contain information from the supplementary reports submitted by prosecuting officials about additional arrests and trials in 2001 arising from intercepts initially reported in prior years. Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 2519(2), prosecutors must submit wiretap reports to the AO no later than January 31 of each year. The AO, in turn, normally publishes the Wiretap Report in April of that year. However, antiterrorism activity following September 11, 2001, and the initiation of the irradiation process for mail sent to the federal government disrupted the U.S. mail service. Many reporting forms prosecutors mailed before January 31, 2002, still had not been received well after the date the AO needed to finish processing all data to meet an April publication deadline. Therefore, the data processing period was extended an additional 30 days so that the 2001 Wiretap Report could include these prosecutors’ reports. Leonidas Ralph Mecham Director May 2002 5 Applications for Orders Authorizing or Approving the Interception of Wire, Oral, or Electronic Communications Reporting Requirements of the Statute the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA). No report to the AO is required when an order is issued with the consent of one of the principal parties to the communication. Examples of such situations include the use of a wire interception to investigate obscene phone calls, the interception of a communication to which a police officer or police informant is a party, or the use of a body microphone. Also, no report to the AO is required for the use of a pen register (a device attached to a telephone line that records or decodes impulses identifying the numbers dialed from that line) unless the pen register is used in conjunction with any wiretap devices whose use must be reported. Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 3126, the U.S. Department of Justice collects and reports data on pen registers and trap and trace devices. Each federal and state judge is required to file a written report with the Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts (AO) on each application for an order authorizing the interception of a wire, oral, or electronic communication (18 U.S.C. 2519(1)). This report is to be furnished within 30 days of the denial of the application or the expiration of the court order (after all extensions have expired). The report must include the name of the official who applied for the order, the offense under investigation, the type of interception device, the general location of the device, and the duration of the authorized intercept. Prosecuting officials who applied for interception orders are required to submit reports to the AO each January on all orders that were terminated during the previous calendar year. These reports contain information related to the cost of each intercept, the number of days the intercept device was actually in operation, the total number of intercepts, and the number of incriminating intercepts recorded. Results such as arrests, trials, convictions, and the number of motions to suppress evidence related directly to the use of intercepts also are noted. Neither the judges’ reports nor the prosecuting officials’ reports contain the names, addresses, or phone numbers of the parties investigated. The AO is not authorized to collect this information. This report tabulates the number of applications for interceptions that were granted or denied, as reported by judges, as well as the number of authorizations for which interception devices were installed, as reported by prosecuting officials. No statistics are available on the number of devices installed for each authorized order. This report does not include interceptions regulated by Regulations The Director of the AO is empowered to develop and revise the reporting regulations and reporting forms for collecting information on intercepts. Copies of the regulations, the reporting forms, and the federal wiretapping statute may be obtained by writing to the Administrative Office of the United States Courts, Statistics Division, Washington, D.C. 20544. The Attorney General of the United States, the Deputy Attorney General, the Associate Attorney General, any Assistant Attorney General, any acting Assistant Attorney General, or any specially designated Deputy Assistant Attorney General in the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice may authorize an application to a federal judge for an order authorizing the interception of wire, oral, or electronic communications. On the state level, applications are made by a prosecuting attorney “if such attorney is authorized by a statute of that State to make application to a State court judge of competent jurisdiction.” 6 Many wiretap orders are related to largescale criminal investigations that cross county and state boundaries. Consequently, arrests, trials, and convictions resulting from these interceptions often do not occur within the same year as the installation of the intercept device. Under 18 U.S.C. 2519(2), prosecuting officials must file supplementary reports on additional court or police activity that occurs as a result of intercepts reported in prior years. Appendix Tables A-2 and B-2 describe the additional activity reported by prosecuting officials in their supplementary reports. Table 1 shows that 46 jurisdictions (the federal government, the District of Columbia, the Virgin Islands, and 43 states) currently have laws that authorize courts to issue orders permitting wire, oral, or electronic surveillance. During 2001, a total of 25 jurisdictions reported using at least one of these three types of surveillance as an investigative tool. numbers used in the appendix tables are reference numbers assigned by the AO; these numbers do not correspond to the authorization or application numbers used by the reporting jurisdictions. The same reporting number is used for any supplemental information reported for a communications intercept in future volumes of the Wiretap Report. The number of wiretaps reported increased 25 percent in 2001. A total of 1,491 applications were authorized in 2001, including 486 submitted to federal judges and 1,005 to state judges. Judges approved all applications. Compared to the number approved during 2000, the number of applications approved by federal judges in 2001 increased 1 percent,1 and the number of applications approved by state judges rose 41 percent. Wiretap applications in New York (425 applications), California (130 applications), Illinois (128 applications), New Jersey (99 applications), Pennsylvania (54 applications), Florida (51 applications), and Maryland (49 applications) accounted for 93 percent of all authorizations approved by state judges. Although the number of states reporting wiretap activity was comparable to the number for last year (24 states in 2001, 25 in 2000), reports were received from 100 separate state jurisdictions in 2001, 15 more than the Summary and Analysis of Reports by Judges Data on applications for wiretaps terminated during calendar year 2001 appear in Appendix Tables A-1 (federal) and B-1 (state). The reporting Federal and State Wiretap Authorizations Number of Authorizations 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 Calendar Year Federal State 7 1998 1999 2000 2001 Federal and State Wiretap Authorizations Percent of Total Authorizations State 58.4% State 67.4% Federal 41.6% Federal 32.6% 1991 2001 taps terminating during 2001, the longest was used in a narcotics investigation in New York County, New York; this wiretap required a 30-day order to be extended 15 times to keep the intercept in operation 431 days. In contrast, 18 federal intercepts and 78 state intercepts each were in operation for less than a week. number of state jurisdictions that reported wiretaps in 2000. Authorized Lengths of Intercepts Table 2 presents the number of intercept orders issued in each jurisdiction that provided reports, the number of amended intercept orders issued, the number of extensions granted, the average lengths of the original authorizations and their extensions, the total number of days the intercepts actually were in operation, and the nature of the location where each interception of communications occurred. Most state laws limit the period of surveillance under an original order to 30 days. This period, however, can be lengthened by one or more extensions if the authorizing judge determines that additional time for surveillance is warranted. During 2001, the average length of an original authorization was 27 days, down from 28 days in 2000. A total of 1,008 extensions were requested and authorized in 2001 (an increase of 9 percent). The average length of an extension was 29 days, up from 28 days in 2000. The longest federal intercept occurred in the District of New Jersey, where an original 30-day order was extended 11 times to complete a 300-day wiretap used in a fraud investigation. Among state wire- Locations The most common location specified in wiretap applications authorized in 2001 was “portable device, carried by/on individual,” a category included for the first time last year in the 2000 Wiretap Report. This category was added because wiretaps authorized for devices such as portable digital pagers and cellular telephones did not readily fit into the location categories provided prior to 2000. Table 2 shows that in 2001, a total of 68 percent (1,007 wiretaps) of all intercepts authorized were for portable devices such as these, which are not limited to fixed locations. The next most common specific location for the placement of wiretaps in 2001 was a “personal residence,” a type of location that includes singlefamily houses, as well as row houses, apartments, and other multi-family dwellings. Table 2 shows that in 2001 a total of 14 percent (206 wiretaps) of all intercept devices were authorized for personal residences. Four percent (60 wiretaps) were authorized for business establishments such as of8 fices, restaurants, and hotels. Combinations of locations were cited in 117 federal and state applications (8 percent of the total) in 2001. Finally, 6 percent (83 wiretaps) were authorized for “other” locations, which included such places as prisons, pay telephones in public areas, and motor vehicles. Since the enactment of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986, a specific location need not be cited in a federal application if the application contains a statement explaining why such specification is not practical or shows “a purpose, on the part of that person (under investigation), to thwart interception by changing facilities” (see 18 U.S.C. 2518 (11)). In these cases, prosecutors use “roving” wiretaps to target a specific person rather than a specific telephone or location. The Intelligence Authorization Act of 1999, enacted on October 20, 1998, amended 18 U.S.C. 2518 (11)(b) so that a specific facility need not be cited “if there is probable cause to believe that actions by the person under investigation could have the effect of thwarting interception from a specified facility.” The amendment also specifies that “the order authorizing or approving the interception is limited to interception only for such time as it is reasonable to presume that the person identified in the application is or was reasonably proximate to the instrument through which such communication will be or was transmitted.” For 2001, authorizations for 16 wiretaps indicated approval with a relaxed specification order under 18 U.S.C. 2518(11). Federal authorities reported that roving wiretaps were approved for two investigations, both authorized for use in drug offense investigations. On the state level, 14 roving wiretaps were reported; 93 percent (13 applications) were authorized for use in drug offense investigations, and one application in a racketeering investigation. that 78 percent of all applications for intercepts (1,167 wiretaps) authorized in 2001 cited drug offenses as the most serious offense under investigation. Many applications for court orders indicated that several criminal offenses were under investigation, but Table 3 includes only the most serious criminal offense named in an application. The use of federal intercepts to conduct drug investigations was most common in the Central District of California (29 applications), the Northern District of Illinois (28 applications), and the Western District of Texas (26 applications). On the state level, the New York City Special Narcotics Bureau obtained authorizations for 117 drugrelated intercepts, which accounted for the highest percentage (16 percent) of all drug-related intercepts reported by state or local jurisdictions in 2001. Nationwide, gambling (82 orders), racketeering (70 orders), and homicide/assault (52 orders) were specified in 5.5 percent, 5 percent, and 3 percent of authorizations, respectively, as the most serious offense under investigation. Summary and Analysis of Reports by Prosecuting Officials In accordance with 18 U.S.C. 2519(2), prosecuting officials must submit reports to the AO no later than January 31 of each year for intercepts terminated during the previous calendar year. Appendix Tables A-1 and B-1 contain information from all prosecutors’ reports submitted for 2001. Judges submitted 35 reports for which the AO received no corresponding reports from prosecuting officials. For these authorizations, the entry “NP” (no prosecutor’s report) appears in the appendix tables. Some of the prosecutors’ reports may have been received too late to include in this report, and some prosecutors delayed filing reports to avoid jeopardizing ongoing investigations. Information received after the deadline will be included in next year’s Wiretap Report. Offenses Violations of drug laws and gambling laws were the two most prevalent types of offenses investigated through communications intercepts. Racketeering was the third most frequently noted offense category cited on wiretap orders, and homicide/assault was the fourth most frequently cited offense category reported. Table 3 indicates Nature of Intercepts Of the 1,491 communication interceptions authorized in 2001, intercept devices were installed in conjunction with a total of 1,405 orders. Table 4 presents information on the average num9 Drugs as the Major Offense 1,200 1,167 1,000 955 876 978 894 870 821 800 732 679 634 600 536 374 400 320 326 285 296 278 1992 1993 1994 328 316 1996 1997 372 296 324 200 0 1991 1995 1998 1999 2000 2001 Calendar Year Drugs Other Offenses ber of intercepts per order, the number of persons whose communications were intercepted, the total number of communications intercepted, and the number of incriminating intercepts. Wiretaps varied extensively with respect to the above characteristics. In 2001, installed wiretaps were in operation an average of 38 days, a 9 percent decrease from the average number of days wiretaps were in operation in 2000. The average number of interceptions per day reported by all jurisdictions in 2001 ranged from less than 1 to over 650. The most active federal intercept occurred in the Central District of California, where a 27-day investigation of copyright infringement related to software piracy involved an electronic wiretap of computers and resulted in an average of 660 interceptions per day. For state authorizations, the most active investigation was a 43-day narcotics investigation in Lubbock County, Texas, that produced an average of 338 intercepts per day. Nationwide, in 2001 the average number of persons whose communications were intercepted per order in which intercepts were installed was 86, and the average number of communications intercepted was 1,565 per wiretap. An average of 333 intercepts per installed wiretap produced incriminating evidence, and the average percentage of incriminating intercepts per order decreased from 23 percent of interceptions in 2000 to 21 percent in 2001. The three major categories of surveillance are wire communications, oral communications, and electronic communications. In the early years of wiretap reporting, nearly all intercepts involved telephone (wire) surveillance, primarily communications made via conventional telephone lines; the remainder involved microphone (oral) surveillance or a combination of wire and oral interception. With the passage of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986, a third category was added for the reporting of electronic communications, which most commonly involve digital-display paging devices or fax machines, but also may include some computer transmissions. The 1988 Wiretap Report was the first annual report to include electronic communications as a category of surveillance. Table 6 presents the type of surveillance method used for each intercept installed. The most common method of surveillance reported was “phone wire communication,” which includes all 10 Arrests and Convictions telephones (landline, cellular, cordless, and mobile). Telephone wiretaps accounted for 83 percent (1,171 cases) of intercepts installed in 2001. Of those, 944 wiretaps involved cellular/mobile telephones, either as the only type of device under surveillance (865 cases) or in combination with one or more other types of telephone wiretaps (79 cases). The next most common method of surveillance reported was the electronic wiretap, which includes devices such as digital display pagers, voice pagers, fax machines, and transmissions via computer such as electronic mail. Electronic wiretaps accounted for 6 percent (84 cases) of intercepts installed in 2001. Microphones were used in 6 percent of intercepts (88 cases). A combination of surveillance methods was used in 4 percent of intercepts (62 cases). Public Law 106-197 amended 18 U.S.C. 2519(2)(b) in 2000 to require that reporting should reflect the number of wiretap applications granted in which encryption was encountered and whether such encryption prevented law enforcement officials from obtaining the plain text of communications intercepted pursuant to the court orders. In 2001, no federal wiretap reports indicated that encryption was encountered. For state and local jurisdictions, encryption was reported to have been encountered in 16 wiretaps in 2001; however, in none of these cases was encryption reported to have prevented law enforcement officials from obtaining the plain text of communications intercepted. Federal and state prosecutors often note the importance of electronic surveillance in obtaining arrests and convictions. The Central District of California reported a federal wiretap that involved cellular telephone surveillance in a narcotics conspiracy investigation that led to 9 arrests; in addition, the reporting officials noted that this wiretap “resulted in the seizure of 223 kilos of cocaine, 7 weapons, 2 vehicles, and $87,580 in cash.” Another wiretap from the same district resulted in the seizure of 25 million dosage units of pseudoephedrine. Reporting officials in the Northern District of Ohio described a federal wiretap in use for 55 days in a narcotics investigation that resulted in 5 convictions, including those of 3 Ohio cocaine distributors and 2 narcotics couriers from California. On the state level, the prosecuting attorney in Lubbock County, Texas, reported that the information obtained in a wiretap using standard and cellular telephone surveillance led to the arrest of 36 persons, 35 of whom were convicted of narcotics offenses, and indicated that “without the intercepts, no prosecutions or few prosecutions would have been possible.” The Georgia State Attorney General reported that a 10-day wiretap approved as part of a racketeering investigation yielded valuable information in an investigation of a telemarketing “boiler room.” The reporting official noted that “the targets of the investigation are suspected of running an illegal magazine sales operation that specifically targets elderly persons. Cases of this nature are inherently difficult to prosecute because of memory and comprehension problems the aged often suffer. The ability of the State to intercept the deceptions as they take place will be invaluable in obtaining convictions in this type of case.” In New Hampshire, the State Attorney General’s office reported that a wiretap in use for 29 days in a drug conspiracy investigation produced 14 arrests, stating that the interceptions were critical evidence in the State’s case, identified numerous sources of the illegal drugs, and “prevented a violent home invasion.” The District Attorney’s Office in Santa Clara County, California, described a 55-day wiretap used in an investigation involving the manufacture of methamphetamine, which resulted in 17 arrests and 2 subsequent convictions. The officials noted Costs of Intercepts Table 5 provides a summary of expenses related to intercept orders in 2001. The expenditures noted reflect the cost of installing intercept devices and monitoring communications for the 1,327 authorizations for which reports included cost data. The average cost of intercept devices installed in 2001 was $48,198, down 12 percent from the average cost in 2000. For federal wiretaps for which expenses were reported in 2001, the average cost was $74,207, a 16 percent increase from the average cost in 2000. However, the average cost of a state wiretap fell 30 percent to $33,650 in 2001. For additional information, see Appendix Tables A-1 (federal) & B-1 (state). 11 Average Cost of Wiretaps (in Dollars) 70,000 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 0 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Calendar Year that the interceptions enabled law enforcement to seize two methamphetamine “super labs,” the locations of which were undetectable without the interceptions; they added that “the sole evidence of culpability against the two persons convicted thus far was the intercepted communications.” Table 6 presents the numbers of persons arrested and convicted as a result of interceptions reported as terminated in 2001. As of December 31, 2001, a total of 3,683 persons had been arrested based on interceptions of wire, oral, or electronic communications, 20 percent (732 persons) of whom were convicted (a decrease from the 2000 conviction rate of 22 percent, but greater than the 1999 conviction rate of 15 percent). Federal wiretaps were responsible for 53 percent of the arrests and 40 percent of the convictions during 2001. A state wiretap in Queens County, New York, resulted in the most arrests of any intercept terminated in 2001. This wiretap was the lead wiretap of six intercepts authorized for use in a larceny investigation that led to the arrest of 103 persons. The Eastern District of Texas produced the most convictions of any federal wiretap when an intercept used in a narcotics conspiracy investigation yielded the conviction of 46 of the 53 persons arrested. The leader among state intercepts in producing convictions was a wiretap that took place in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, and was the lead wiretap of three used in homicide and narcotics investigations. This wiretap led to 43 arrests and 39 convictions. Because criminal cases involving the use of surveillance may still be under active investigation, the results of many of the intercepts concluded in 2001 may not have been reported. Prosecutors will report the costs, arrests, trials, motions to suppress evidence, and convictions related directly to these intercepts in future supplementary reports, which will be noted in Appendix Tables A-2 and B-2 of subsequent volumes of the Wiretap Report. Summary of Reports for Years Ending December 31, 1991 Through 2001 Table 7 provides information on intercepts reported each year from 1991 to 2001. The table specifies the number of intercept applications requested, denied, authorized, and installed; the number of extensions granted; the average length of original orders and extensions; the locations of intercepts; the major offenses investigated; average costs; and the average number of persons intercepted, communications intercepted, and 12 incriminating intercepts. From 1991 to 2001, the number of intercept applications authorized increased 74 percent. The majority of wiretaps involved drug-related investigations, ranging from 63 percent of all applications authorized in 1991 to 78 percent in 2001. ecution activity by jurisdiction for intercepts terminated in the years noted. Most of the additional activity reported in 2001 involved wiretaps terminated in 2000. Intercepts concluded in 2000 led to 65 percent of arrests, 54 percent of convictions, and 89 percent of expenditures reported in 2001 for wiretaps terminated in prior years. Table 9 reflects the total number of arrests and convictions resulting from intercepts terminated in calendar years 1991 through 2001. Supplementary Reports Under 18 U.S.C. 2519(2), prosecuting officials must file supplementary reports on additional court or police activity occurring as a result of intercepts reported in prior years. Because many wiretap orders are related to large-scale criminal investigations that cross county and state boundaries, supplementary reports are necessary to fulfill reporting requirements. Arrests, trials, and convictions resulting from these interceptions often do not occur within the same year in which the intercept was first reported. Appendix Tables A-2 and B-2 provide detailed data from all supplementary reports submitted. During 2001, a total of 2,670 arrests, 2,112 convictions, and additional costs of $10,571,236 were reported from wiretaps completed in previous years. Table 8 summarizes additional pros- Endnote 1 In 2001, the reporting of some wiretaps conducted by federal organizations was delayed. Records from some U.S. Customs Service (USCS) investigations conducted in the New York City area were destroyed along with the USCS’s facility in the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Because of this loss, data on USCS cases for the New York region that involved Title III electronic surveillance were not available to be reported in the 2001 Wiretap Report. Any wiretap data that can be recreated will be reported later and will appear in a subsequent volume of the Wiretap Report. 13