Journal 7-3

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

A PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN C1VllllB~R'rIES UNION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOL 7, NO.3, SUMMER 1992 • ISSN 0748·2655

)\,

"

ABA Report Urges Reform in Sentencing, Corrections

n the eve of the April 1992

"Corrections Summit" sponsored

by Attorney General William

Barr, the American Bar Association

(ABA) released a new report, The Use

ofIncarceration in the United States:

A Look at the Present and the Future

by Professor Lynn S. Branham. Unfortunately, the report was nearly lost in the

glare of the Summit's political motivations and arrived too late to challenge

the Bush Administration's claim that we

must choose between "more prison

space or more crime." Rather than spend

tax dollars on an expensive conference

with questionable results, Summit

organizers would have done well to

simply send participants a copy of this

comprehensive and valuable report.

The ABA report is written with

members of state and local bars in

mind, and urges them to assume

responsibility for pushing sentencing

and correctional reform. However, it

offers important food for thought for

anyone with a role in corrections, be

they lawyers, corrections officials,

community'groups, legislators, judges

or otherwise.

The report is divided into three

sections. The first one provides a clear

and detailed picture of incarceration

today. Recommendations for reform

follow in section two. The report concludes by advising state and local bars to

work for reform with suggestions on how

they might do so effectively. An Appendix

includes the full text of the ABA's Model

Community Corrections Act which was

approved by the ABA's House of Delegates

in February 1992.

One characteristic which sets this

report apart is its sense of balance and

the lack of a hidden agenda. Professor

O

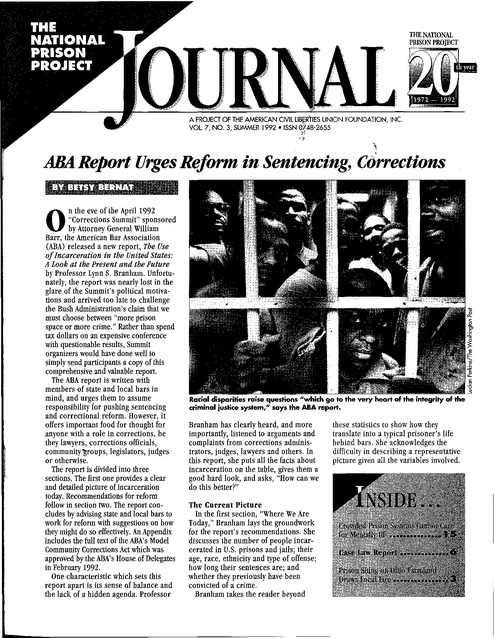

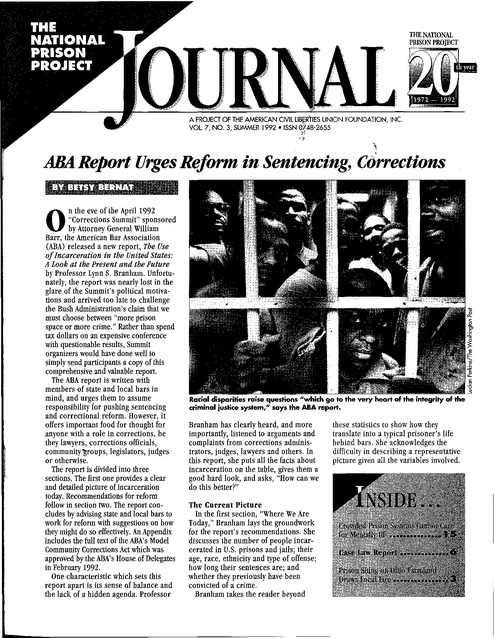

Racial disparities raise questions "which go to the very heart of the integrity of the

criminal justice system," says the ABA report.

Branham has clearly heard, and more

importantly, listened to arguments and

complaints from corrections administrators, judges, lawyers and others. In

this report, she puts all the facts about

incarceration on the table, gives them a

good hard look, and asks, "How can we

do this better?"

The Current Picture

In the first section, "Where We Are

Today," Branham lays the groundwork

for the report's recommendations. She

discusses the number of people incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails; their

age, race, ethnicity and type of offense;

how long their sentences are; and

whether they previously have been

convicted of a crime.

Branham takes the reader beyond

these statistics to show how they

translate into a typical prisoner's life

behind bars. She acknowledges the

difficulty in describing a representative

picture given all the variables involved.

IT'

I

I:

I

Chances are good, though, that the facility

is overcrowded, the prisoner is idle much

of the time, has little or no privacy, and

must find some way to protect himself

against physical attacks. This section

would be further enhanced by a similar

discussion of what life is like for a

typical correctional officer in an

overcrowded and understaffed facility.

Branham offers five key reasons why,

based on her research, more people are

incarcerated today.l The crime rate is

not the culprit. According to the

National Crime Survey, the level of

crime was 14.5% lower in 1990 than in

1980 and was fairly stable in the years

in between; yet, in the same ten years,

the prison population grew by 133.8%.

The population increase can be better

explained by the folloWing: 1) a higher

percentage of people are being sentenced to prison for crimes that, at one

time, either would not have been

prosecuted or would have resulted in a

non-incarcerative sentence; 2) longer

sentences are being imposed for some

crimes (though Branham points out that

sentence lengths are due for some upto-date analysis); 3) more restrictive

parole and release policies; 4) increased probation and parole revocations (Le., in 1978, 8% of prison

admissions in California were parole

violators; in 1988, 45%); and 5)

demographic factors. From 1974 to

1986, the national population experienced a double-digit increase in the

number of people in their 20s (the

prison-prone years).

The costs and benefits of all this

incarceration, under Branham's

scrutiny, yield some surprises. For

instance, in 1991, the average cost to

incarcerate a prisoner for one year was

reported as $17,545.55. However, the

report notes, this figure omits costs

such as pensio'hs for correctional

officers and contract mental health

care. Weighing all factors, the annual

expense reaches $30,000 per inmate.

What does this mean for state budgets

and for taxpayers? In Delaware, it takes

all of the state income tax paid by 18

residents to keep just one state prisoner

incarcerated for a year. In California in

1990, when the state's prison population experienced the sharpest increase

in the country, the legislature cut the

education budget by $2 billion to pay

for more prisoners.

With so many people incarcerated, is

the country safer? The answer is no, and

Branham cites supporting crime

2 SUMMER 1992

statistics and several reports on

recidivism and criminal incapacitation

as proof.

Twelve Recommendations

Having given us the bad news,

Branham follows with some good news

in the form of 12 recommendations

which "hold the promise of making our

criminal-punishment system more

effectual." Branham rescues the

recommendations from becoming mere

rhetoric by substantiating them with

detailed work plans and reports.

The recommendations-abbreviated

here-suggest that states and localities:

1. Adopt a comprehensive community

corrections act, to include a broad

range of sanctions for non-Violent

offenders to be used not only at

sentencing but also when sanctioning

parole and probation violators. The

ABA's Model Adult Community

Corrections Act, attached to the

report as an Appendix, provides a

detailed plan for developing and

implementing such a program.

2. Adopt sentencing guidelines which

include a range of community-based

sanctions.

3. Draft sentencing guidelines to ensure

that prison space is generally reserved for violent offenders.

4. Expand the use of means-based fines.

Fines are widely used with much

success in other countries.

5. Allow for a graduated response,

within a sentencing system, to a

violation of a community-based

sanction or parole. Prison need not

be the automatic response. Sanction

options, which become more severe

depending on the level of offense,

include restricted mobility in the

community, increased supervision,

special conditions, and financial

penalties.

6. Repeal mandatory minimum sentences. Branham notes, "These

statutes are the product of what has

practically become a shoving match

between politicians to demonstrate

who is the toughest on crime."

7. Prepare correctional impact statements

before enacting legislation which would

raise the number of people under

correctional supervision. These

statements should forecast the

legislation's effect in terms of prison

space, staff, programs and costs.

8. Require sentencing guidelines

commissions to draft and adjust

sentencing gUillelines which are

commensuratl("iwith the capacity of

the jurisdictiJ5h's correctional system.

9. Provide a range of programseducational, vocational, mentalhealth, substance abuse treatment,

counseling, and others-in order to

reduce recidivism. These programs

should be fully funded and of high

quality.

Branham understands that many

Americans object to the idea of providing job training to prisoners when their

own access to these programs is

limited. She offers a convincing "pay

now or pay later" argument in which

Editor: Jan Elvin

Editorial Asst.: Betsy Bernat

Alvin J. Bronstein, Executive Director

The National Prison Project of the

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, #410

Washington, D.C. 20009

(202) 234-4830 FAX (202) 234-4890

The Natianal Prisan Project is 0 tax-exempt foundationfunded project of the ACLU Foundation which seeks to

strengthen and protect the rights of adult and juvenile

offenders; to improve overall conditions in correctional

facilities by using existing administrativel legislative and

judicial channels; and to develop alternatives to

incarceration.

The reprinting of JOURNAL material is encouraged with

the stipulation that the National Prison Project JOURNAL

be credited with the reprint, and that a copy of the reprint

be sent to the editor.

The JOURNAL is scheduled for publication quarterly by

the National Prison Project. Materials and suggestions

are welcome.

TheNPPJOURNAL is available on 16mm

microfilm, 35mm microfilm and 105mm

microfiche from University Microfilms

International, 300 North Zeeb Rd., Ann

Arbor, MI 48106-1346.

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEG JOURNAL

I

[

.:.j

she notes that if we don't pay for these

programs while the prisoner is incarcerated, chances are that we'll be

paying for his incarceration all over

again later on.

10.Inmates who are not going to school

full-time should work while incarcerated.

11. Develop release programs to help

ensure a prisoner's successful

return to life on the "outside."

12. Earmark at least 3-5% of a corrections budget for research to study

the system's effectiveness and costefficiency. Branham also emphasizes

the need for more research into

racial and ethnic disparity in the

criminal justice system. Evident

disparities raise "questions...which

go to the very heart of the integrity

of the criminal justice system."

corrections and sentencing committees;

working with ABA committees and other

organizations; offering to educate

judges, defense attorneys and prosecutors on community-based sanctions;

educating the public about corrections

and sentencing issues; and, finally,

monitoring corrections legislation and

operations.

The Role of State and Local Bars

More Valuable Information

Betsy Bernat is editorial assistant of

the NPP JOURNAL.

The ABA report concludes by urging

members of state and local bars to

shoulder their share of responsibility

toward implementing correctional

reform. They can do so by establishing

Thirteen pages of excellent references

follow the body of the report. Branham

concludes the ABA report by urging an

overhaul of sentencing and corrections

systems. Such an overhaul, she notes,

I This section opens with a useful explanation of why

there is so much variation between the crime rates

reported by the National Crime Survey and the

Uniform Crime Report.

must stress "accountability: ...accountability of offenders to their victims and

society and accountability of government officials...to the public."

Finally, she says, "Reform only occurs

through hard work and over time. And

now is the time for the hard work of

reforming the nation's sentencing and

corrections systems to begin." •

Citizens Protest Taking of Farmland

for Federal Prison Site

"A 900-acre tract near Elkton

[OhioJ has been chosen as the site for

a 2, 750-bed federal prison to be built

here, bringing with it between 650

and 850 jobs that pay an average of

$26,000 a year."

n Janlhlry 9, 1992, landowners

and farmers in Columbiana

County, Ohio awoke to this news

on the front page of the local Morning

journal. The newspaper article further

stated that, since the Bureau of Prisons

requires that the property for the prison

be donated, the county would offer

property owners fair market value for

their land. Should landowners refuse

the offer, the county could still confiscate the land through the right of

eminent domain. This will happen, say

the landowners, over their dead bodies.

The proposed federal prison has

created a controversy and pitted

Columbiana Countians against each

O

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

other. Since January, county and state

officials have come under heavy fire

from landowners as it has become

evident that many of the officials knew

of the plans to build before the announcement was made public. Affected

landowners were kept completely in

the dark.

In fact, opponents of the prison

accuse officials of secretly courting the

Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to

secure the property as the site of the

prison, then deliberately waiting to

announce the choice publicly until the

deed was as good as done.

Residents opposed to the building of

the prison also claim that Morning

journal readers are not getting objective reporting, and that the newspaper's

reports are intended to sway the

citizenry in favor of the prison. The

paper's publisher, John Burgess, has

been a strong and public supporter of

the prison. Indeed, a review of the

The Use ofIncarceration in the

United States\ A Look at the Present

and the Futur~, by Professor Lynn S.

Branham, is ~ailable from ABA Order

Fulfillment,"750 North Lake Shore

Drive, Chicago, IL 60611, 312/988-5555

for $8.75 prepaid ($7.00 for ABA Criminal Justice Section members), checks

payable to American Bar Association.

Please request Order #5090051.

paper's headlines suggests a bias in

favor of the building of the prison:

"County's economy will get big

boost;"

"County effort [to bring prison] draws

praise from governor;"

"Prison will mean 1,000 jobs for

county;"

"Opposition could spell prison loss,

officials say;"

"Council celebrates progressive start"

(refers to "its first accomplishmentluring a federal prison to a site outside

of Elkton").

Landowners would undoubtedly write

the headlines differently, if they could.

They are fighting hard to keep their

land, and they vow that the federal

government will never take it from

them. They have formed a grassroots

organization called Columbiana

Countians Against the Prison (CCAP),

and are, according to their literature,

"united in our love and care and

protection of the land that feeds our

entire nation."

CCAP members claim that the BOP

refuses to give straight answers to their

many questions; that the information

they do get changes almost weekly, and

that the resulting confusion only adds to

(cont'd on page 4)

SUMMER 1992 3

Farmers in Columbiana County plowed this message into their land for the benefit of government photographers taking

pictures for an environmental impact statement.

their feelings of frustration and helplessness. The Bureau's estimate of the

number of affected property owners has

gone from the originally stated 12, to 58

only two months later. The number of

prisoners they claim will be held there

has also varied, from the original 2,750

to the latest count of 4,800.

Loss of Family Farmland

where I figured I would spend the rest

of my life. Now, 1 don't know."

"It's one thing," wrote Shirley

Mondak in the local paper, "to lose a

place because you've fallen behind in

taxes, but these families have hung on

and kept their farms and properties

despite some very staggering odds.

They've done it the American wayearning the land and working the land,

"We're nothing to you guys," Lori

Garn angrily told county commissioners

at one January meeting. Garn's family

owns 82 acres on Scroggs Road, which

runs through the property.

"There's a lot of me in that ground up

there," said Richard Scroggs, who lives

in the family home that was built in

1832 on the road named after his

ancestors.

Morris Boles, 62, lives near the

cemetery on Church Hill Road where his

parents and grandparents, who had also

farmed the land, are buried. "I remodeled the house several years ago and got

it all lined up for my retirement," says

Boles of his 72-acre farm. "This was

maintaining its use and its beauty."

There are two historical homes

located on the site and over 600 acres

of tillable, fertile farmland.

Bureau officials have apparently

rej ected a nearby site which is reclaimed mining land because of the

distance from sewage hookups and

water resources.

4

SUMMER 1992

Jobs

State and county officials are looking

forward to an economic boom brought

about by the building of the prison.

According to county commissioner Don

Lowe, other areas where federal prisons

have been built, such as Lewisburg,

Pennsylvania, have boomed economically.

Another commissioner said, "This is

one of the greatest shots in the arm

we've had in a long time. This might be

a better benefit than Lordstown (GM

plant) because this is recession-proof."

County commissioner John Wargo

states, "I think financially the impact will

be profound." Federal officials have told

Wargo that two new "outside" jobs are

usually generated for every prison job.

Columbiana Countians Against

the Prison (CCAP)

Every Monday night CCAP holds

strategy meetings at the County Career

Center, drawing 100-150 locals who are

upset about the prison. An attorney who

specializes in farmers' rights has been

hired by CCAP. The group has also

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

Lori Garn, who owns 82 acres in the vicinity of the planned prison, speaks out at a local meeting.

formed eight committees, begun a petition

drive by citizens and businesses, started a

public information campaign, mounted

store displays, and initiated a speakers'

bureau. Aresearch committee was

formed to ensure the accuracy of information being disseminated. One member

said, "We used to have lives here. Now all

we do is work on this."

I

I

!I

11

I"

II

The Bureau of Prison's View

"We are sensitive to their concerns,"

said Debra Hood, site selection and

environmental review specialist for the

BOP, "but the Bureau has a mission. With

the overcrowded conditions in the federal

prisons, we have to look at expansion."*

When asked why the Bureau picked

the Elkton site in Columbiana County for

the new prison, Hood told the NPP

JOURNAL that county and state offiCials,

as well as a congressional delegation,

had solicited the Bureau for this site. In

addition, she said that BOP projections

show that "the largest number of federal

offenders will come from their region."

She said that the level of resistance to

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJE0 JOURNAL

the prison that they have encountered

to date in Columbiana County is not

unusual. "It's the 'Not in My Back Yard'

syndrome," said Hood. "To us, opposition is opposition. The final decision on

where to locate the prison rests with

[Bureau of Prisons] Director Quinlan."

Environmental Concerns

The fact that the land belongs to them

is not the only reason CCAPers are

opposed to the prison site, however.

CCAP also has questions about the

impact of a 4,800-bed prison on the

water supply, sewage and utility

availability, fire protection (the area is

served by one small volunteer fire

department), and deep mines.An

environmental impact statement done by

the government should be available for

public review by the late fall.

Growing Anger

from Local Residents

At more than one meeting, furious

crowds of 250-300 homeowners, all

who live either on the site or its

perimeter, have gathered to voice

opposition to the prison.

"So we're screwed," yelled one man.

"Dictators," shouted another over and

over.

In addition to petition drives, confrontational meetings, strategy sessions

with attorneys, and sophisticated public

education campaigns, CCAP members

have also relied on traditional organizing methods with an Ohio flair to them.

To raise money for their cause they have

organized pig raffles and held rummage

sales and bake sales.

(cont'd on page 14)

SUMMER 1992 5

rt

A PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN C1VllllBERTIE~,UNION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOL 7, NO.3, SUMMER 1992 • ISSN 0748-6~55

Highlights of Most

Important Cases

Exhaustion of RemedieslFederal

Officials and Prisons!Access to

Courts

Prisoners' remarkable winning (or at least

non-losing) streak in the 1991-92 Supreme

Court term continued in McCarthy v.

Madigan, 112 S.Ct. 1081 (1992).

In previous decisions this term, the

Supreme Court refused significantly to worsen

the law governing use of force (Hudson v.

McMillian) or the modification of injunctive

judgments governing jail conditions (Rufo v.

Inmates ofthe Suffolk County]ail). In

McCarthy, the Court held unanimously (with

Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices Scalia and

Thomas concurring in the result) that federal

prisoners seeking only damages in a "Bivens

action" need not exhaust their administrative

remedies in the Bureau of Prisons, which do

not prOVide for damages, before resorting to

federal court. (Constitutional damage suits

against federal officials are commonly called

"Bivens actions" after the Supreme Court case

that allowed them despite the absence of an

authorizing statute similar to 42 U.S.C. §1983.

See Bivens v. Six Unknown Federal Narcotics

Agents, 403 u.S. 388 [1971].)

It has long been established that state

prisoners proceeding under §1983 need not

exhaust administrative remedies, except in a

limited category of cases governed by the Civil

Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act. Patsy

v. Board ofRegents ofState ofFlorida, 457

u.S. 496 (1982). Federal prisoners, however,

have consistently been subject to an administrative exhaustion requirement, at least in

cases where the relief the prisoner sought

could be obtained through the administrative

process. See Lyons v. U.S. Marshals, 840 F.2d

202,204 (3d Cir. 1989); Payne v. Day, 440

F.Supp. 785, 787-88 (W.D.Okla. 1977) and

cases cited.

6 SUMMER 1992

The rule the Court overturned in

McCarthy went one step further and

required prisoners to exhaust administrative

remedies even if those procedures could not

prOVide the money damages the prisoner

sought. This rule has its origins in Brice v.

Day, 604 F.2d 664 (10th Cir. 1979), cert.

denied, 444 u.S. 1086 (1980), and was

justified by the supposed necessity preliminarily to develop the facts so the court could

determine whether permitting a "Bivens

action" was appropriate. The Brice court

also stressed the need to reinforce the

authority of prison officials and their chain

of command.

Brice was decided before Carlson v.

Green, 446 u.S. 14 (1980), in which the

Supreme Court first upheld the availability

of a Bivens action to a prisoner claiming an

Eighth Amendment violation, and tacitly

affirmed that Bivens is presumptively

applicable to all constitutional claims.

Before Carlson, some lower courts had

proceeded gingerly in extending the Bivens

doctrine beyond the Fourth Amendment

police misconduct context of Bivens itself.

Neverthless, even at the time, the Brice

holding seemed to some more like an

exercise in docket-clearing than a reasoned

adjudication, and it was not widely followed.

Justice Blackmun's opinion in McCarthy

canvasses the law of administrative exhaustion at some length, but its analysis is

ultimately simple. "Where Congress

specifically mandates, exhaustion is

required.... But where Congress has not

clearly reqUired exhaustion, sound judicial

discretion governs." 112 S.Ct. at 1086. This

judicial discretion reqUires consideration of

the courts' '''virtually unflagging obligation'

to exercise the jurisdiction given them" by

Congress, 112 S.Ct. at 1087 (citation

omitted), and balancing of "the interest of

the individual in retaining prompt access to

a federal judicial forum against

countervailing institutional interests favoring

exhaustion." Id.

Applying these principles, the Court found

that Congress had not specifically mandated

exhaustion. The Court refused to find an

exhaustion requirement in the general

delegation of autjlOrity to the Attorney

General to adm~ister the federal prison

system. Nor was' it convinced by prison

officials' rather perverse argument that the

Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act,

which applies only to state prisoners,

somehow supports an exhaustion requirement for federal prisoners as well.

Balancing the interests at stake, the Court

held that the prisoner's interest in avoiding

the exhaustion requirement is great. The

risk of forfeiting a claim by missing one of a

succession of rapid filing deadlines,

combined with the unavailability of damages

in the administrative scheme, creates a

situation in which the prisoner seeking only

damages "has everything to lose and nothing

to gain" from an administrative exhaustion

requirement. 112 S.Ct. at 1090. Nor does

the Bureau of Prisons have weighty interests

in favor of administrative exhaustion, other

than its generalized interest in "encouraging

internal resolution of grievances and in

preventing the undermining of its authority

by unncessary resort by prisoners to the

federal courts." 112 S.Ct. at 1092. The

subject matter of the suit-failure to

provide medical care-has little bearing on

the Bureau's ability to control and manage

the prisons, and the Bureau "does not bring

to bear any special expertise" on the issues

presented in the case.

The McCarthy holding is limited to those

cases in which the plaintiff seeks damages and

nothing else; the plaintiff conceded that the

analysis would be different if his complaint

sought an injunction, and the lower federal

courts agree that exhaustion is required in

such cases. Terrell v. Brewer, 935 F.2d 1015,

1019 (9th Cir. 1991) and cases cited.

McCartby's implications go beyond its

narrow holding.

First, McCarthy should have a significant

impact on the application of the Civil Rights

of Institutionalized Persons Act ("CRIPA")

to the claims of state prisoners. At least one

lower court has held that CRIPA reqUires

prisoners seeking damages to exhaust

grievance procedures that do not provide

for damages. Martin v. Catalanotto, 895

F.2d 1040, 1042 (5th Cir. 1990). Justice

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

----------_._-----

Blackmun in McCarthy observed that CRIPA

requires exhaustion only of "effective

administrative remedies" and makes clear

his view (supported by earlier observations

by the Department of Justice) that an

administrative remedy must provide

damages to be deemed "effective" relative to

a damage lawsuit. 112 S.Ct. at 1089 and n.

4. Since this discussion is integral to the

Court's dismissal of CRIPA as supporting a

federal prisoner exhaustion requirement, it

cannot be dismissed as dictum, and appears

clearly to overrule Martin v. Catalanotto.

Second, the Court's opinion gives no

credence to the growing hostility to prisoner

claims as a class, readily apparent in the

lower courts after eleven years of purposefully conservative judicial appointments.

See, e.g., Long v. Collins, 917 F.2d 3,4

(5th Cir. 1990) (referring to "current

misallocation of social resources toward

excessive prisoner litigation"); Martin v.

Catalanotto, 895 F.2d at 1040 (complaining about "inund[ation]" with prisoner

claims); Scher v. Purkett, 758 F.Supp.

1316,1317 (E.D.Mo. 1991) (denouncing

"inmate knavery" and "malcontent inmates"

complaining about "petty deprivations").

But the Court in McCarthy treats the technical

exhaustion question in a technical manner

without reference to any perceived problem

presented by prisoner claims as a class.

(Indeed, so does Chief Justice Rehnquist's

opinion concurring in the result.)

More pointedly, the McCarthy Court

reaffirmed the view it stated in 1980 in

Carlson v. Green that the Bivens remedy

should be no less available to prisoners than

to other litigants:

... [Rjespondents appear to confuse the

presence of special factors with any

factors counseling hesitation [in

allowing a Bivens suit]. In Carlson, the

Court held that "specialfactors" do

not free prison officials from Bivens

liability, because prison officials do

not enj8Y an independent status in

our constitutional scheme nor are they

likely to be unduly inhibited in the

performance oftheir duties by the

assertion ofa Bivens claim.

112 S.Ct. at 1090 (citation omitted)

(emphasis in original).

Finally, a throwaway line in the McCarthy

opinion may ultimately influence the

development of the law of prisoners' access

to courts. In describing the danger of

procedural forfeiture of claims posed by the

Bureau of Prisons' administrative remedy

scheme, the Court noted:

The 'first" of "the principles that

necessarily frame our analysis of

prisoners' constitutional claims" is

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

that 'federal courts must take

cognizance of the valid constitutional

claims ofprison inmates." Turner v.

Safley,.... Because a prisoner ordinarily

is divested ofthe privilege to vote, the

right to file a court action might be

said to be his remaining "most

;'

fundamental political right, becausfJ;

preservative ofall rights." Yick Wo:y.

Hopkins,....

. .

112 S.Ct. at 1091.

.

)•.t,

The important question that may b~;;

affected by this observation is the relationship between the "reasonable relationship"

standard, articulated in recent Supreme

Court decisions involVing prisoners' First

Amendment and substantive due process

claims, and the requirement of Bounds v.

Smith, 430 U.S. 817, 822 (1977), that

prisoners' means of access to courts must

be "adequate, effective, and meaningful."

The Court held in Turner v. Safley, and has

reiterated forcefully, that the reasonable

relationship standard "applies to all

circumstances in which the needs of prison

administration implicate constitutional

rights." Washington v. Harper, 494 U.S.

210,224 (1990). Under the Turner

standard, the plaintiff must "point to an

alternative that fully accommodates the

prisoner's rights at de minimis cost to valid

penological interests.... " 482 U.S. at 91; see

Jordon v. Gardner, 953 F.2d 1137, 1141

(9th Cir. 1992) (plaintiff must suggest

"costless alternative"), rehearing granted.

F.2d, 1992 WI. 155760 (9th Cir., July 7,

1992); Blankenship v. Gunter, 898 F.2d

625, 628 (8th Cir. 1990) (alternatives

requiring "little or no effort" required). But

anyone familiar with prison operations

knows that accommodating the right of

court access is one of the most expensive

services that prisoners receive, because of

the inordinate costs of purchasing and

maintaining law libraries or providing

trained legal assistance and the administrative difficulties of making either alternative

meaningfully available to all prisoners

(including segregated populations) who

require them. If the Turner standard were

applied literally to court access claims, and

Bounds deemed limited by it, prison officials

might well be permitted severely to curtail

their law library or legal assistance programs.

To date, courts have not taken that

approach. Indeed, at least two courts have

explicitly rejected the application of Turner

to court access claims, albeit for different

reasons.

In Griffin v. Coughlin, 743 F.Supp. 1006,

1022 n. 15 (S.D.N.Y. 1990), the court held

that the Turner factors are appropriately

applied only to those rights "for which the

----~----------

original interpretation arose outside a

prison setting," unlike court access, a right

that is chiefly an artifact of the restrictions

imposed by incarceration. The problem with

this argument is that there are plenty of

court access cases that arise outside prison.

See, e.g., California Motor Transport Co. v.

Trucking Unlimited, 404 U.S. 508, 513

(1972); Chrissy F. by Medley v. Mississippi

Dept. ofPublic Welfare, 925 F.2d 844, 851

(5th Cir. 1991); Harrison v. Springdale

Water and Sewer Commission, 780 F.2d

1422, 1427-~ (8th Cir. 1986); Bell v. City

ofMilwauke'(j, 746 F.2d 1205, 1260-61 (8th

Cir. 1984) ./fhe historical accident that

prisoners' court access cases may have been

decided earlier than those of non-prisoners

hardly seems a convincing basis for

distinguishing the right to court access from

other rights in which the time sequence was

different. Moreover, the premise that the

"original interpretation" of the right of

court access arose in prison cases is itself

questionable. Some courts have traced the

right (if not the precise phrase "access to

courts") as far back as 1907. See Ryland v.

Shapiro, 708 F.2d 967,971 (8th Cir. 1983),

citing Chambers v. Baltimore & Ohio

Railroad, 207 U.S. 142, 148 (1907).

In Abdul-Akbar v. Watson, 775 F.Supp.

735,748 (D.Del. 1991), the court held that

Turner does not apply because the right of

court access places affirmative obligations

on prison officials, and the Turner standard

applies only to restrictions on rights. This

distinction, too, is problematical. In the

regimented setting of prison life, the

exercise of most rights-including correspondence, marriage, and religious

observance, to which the Supreme Court has

already applied the Turner standardplaces affirmative obligations on prison

offiCials, e.g., to hire clergy and prOVide for

delivery of mail.

McCarthy v. Madigan prOVides support at

least in dictum for a third approach: that the

fundamental role of court access in

preserving all rights makes it qualitatively

different from other rights and justifies

excepting it from the "one size fits all"

approach of Turner and Washington v.

Harper. This approach has the virtue of

concreteness and practicality and does not

rely on distinctions that may not survive

close analysis.

In Forma Pauperis

Prisoners' Supreme Court string ran out

in Denton v. Hernandez, 112 S. Ct. 1728

(1992), in which the Court tried and

seemingly failed to give content to its prior

holding that "claims describing fantastic or

delusional scenarios" are sufficiently

SUMMER 1992 7

"baseless" to be considered frivolous, and

therefore ineligible for in forma pauperis

status, under 28 U.S.C. §1915(d). See

Neitzke v. Williams, 490 U.S. 319, 327-28

(l989).

Mr. Hernandez had filed several civil rights

suits alleging that he had been drugged and

raped 28 times by both inmates and staff

members in various California prisons. He did

not claim to remember any of these incidents,

but inferred most of them from the presence

of needle marks on his body and fecal and

semen stains on his clothes. However, three of

the incidents were supported by affidavits

from other prisoners who stated that they

witnessed the plaintiff being sexually assaulted

by other prisoners.

The district court dismissed the plaintiff's

claims as frivolous on the ground that,

considered together, his allegations were

"wholly fanciful." Adivided panel of the Ninth

Circuit reversed, with one judge holding that a

claim may not be dismissed as frivolous on

factual grounds unless the factual allegations

are in conflict with facts that are subj ect to

judicial notice. 861 F.2d at 1426. One judge

concurred in the result on procedural

grounds, and the other panel member (a

Third Circuit judge sitting by designation)

dissented, emphasiZing that the plaintiff had

been transferred from prison to a mental

hospital for psychiatric treatment and arguing

that the purpose of prisoner civil rights

actions "should not be prostituted by the

hallucinations of a troubled man."

The Supreme Court granted certiorari and

vacated the judgment in light of Neitzke v.

Williams, 490 U.S. 319 (l989). On remand

the appellate judges adhered to their views,

with one modification: the author of the

majority opinion stated the general standard

for dismissal as "delusional" or "hallucinatory" is whether the complaint "rests upon

facts which the court knows could not have

occurred." Contradiction of judicially

noticeable facts is "one useful standard" in

determining wh~her allegations are

"fanciful." 929 F.2d at 1376. The Supreme

Court again granted certiorari "to consider

when an in forma pauperis claim may be

dismissed as factually frivolous under

§1915(d)." 112 S.Ct. at 1732.

The Supreme Court vacated and remanded, rejecting the appeals court's

reasoning and stating that "a finding of

factual frivolousness is appropriate when

the facts alleged rise to the level of the

irrational or the wholly incredible, whether

or not there are judicially noticeable facts

available to contradict them." 112 S.Ct. at

1733. However, the Court provided little

guidance to the lower courts in determining

whether allegations are "irrational,"

8 SUMMER 1992

"incredible," "fanciful," "delusional" or

"hallucinatory." It stated that "the district

courts, who are 'all too familiar' with factually

frivolous claims,...are in the best position to

determine which cases fall into this category."

Id. at 1734. Accordingly, it held that the

appeals court had erred by reviewing the

district court's finding of frivolousness de

novo, and should instead have reviewed the·,case only for an abuse of discretion. The ca~~

was remanded for "proceedings consistent 'jx

with this opinion." It may still be open to thll

appeals court to find that the district court

did abuse its discretion.

'

Thus, after two Ninth Circuit opinions and

two trips to the Supreme Court, there is still

no resolution of whether this case, filed in

1984, will be permitted to proceed in forma

pauperis. Nor has the Supreme Court

provided any meaningful guidance to the

lower courts in making the initial decision

of factual frivolousness.

The difficulty of this question in some

cases cannot be overstated, since the reality

of American prison life approaches the

"fantastic" or "delusional" more often than

anyone wishes to acknowledge. See, e.g.,

Parrish v. Johnson, 800 F.2d 600,605 (6th

Cir. 1986) (awarding damages against

officer who verbally taunted paraplegic

prisoner, waved a knife in his face, and

extorted food from him); Oses v. Fair, 739

F.Supp. 707, 709 (D.Mass. 1990) (awarding

damages to a prisoner against an officer

who struck him with a gun, stuck the gun

barrel into his mouth, and made him kiss

the officer's wife's shoes).

The practical effect of the decision may be

to insulate from review unjustified dismissals of possibly meritorious prisoner

complaints. The federal appeals courts

regularly reverse lower court decisions

holding prisoner claims (usually pro se

complaints) frivolous even though they

clearly state well-recognized constitutional

claims. See, e.g., LaFevers v. Saffle, 936

F.2d 1117,1119-20 (lOth Cir. 1991)

(denial of religious diet); In re Cook, 928

F.2d 262 (8th Cir. 1991) (denial of medical

care); Frazier v. DuBois, 922 F.2d 560,

561-62 (lOth Cir. 1990) (transfer in

retaliation for constitutionally protected

activities); Abdul-Akbar v. Watson, 901

F.2d 329, 334 (3d Cir. 1990 (denial of

access to courts); Moreland v. Wharton,

899 F.2d 1168,1170 (11th Cir. 1990)

(denial of medical care); Lawler v.

Marshall, 898 F.2d 1196, 1199 (6th Cir.

1990 (knOWing failure to protect from other

inmates). It appears in many such cases that

the district court simply paid too little

attention to the actual allegations of the

prisoner's complaint, did not seriously

consider their legal viability, or made

credibility judgments that are not appropriate at that stage of the proceeding. See

Brownlee v. Conine, 975 F.2d 353, 355

(7th Cir. 1992) (Posner, J.) ("Most

prisoner civil rights cases are frivolous, but

district judges, busy as they are, must not

assume that all are and dismiss them by

note. They may not throw out the haystack,

needle and all.")

The Supreme Court's endorsement of a

less exacting standard of appellate review

will most probablYllead to more affirmances

of such dismissal~ resulting both in

injustice to the .alfected individuals and to a

further deterioration of quality control in

the face of a significant pattern of perfunctory lower court adjudication.

Other Cases

Worth Noting

U.S. COURT OF APPEALS

Telephones/Assistance

of CounseVMedical Care

Tucker v. Randall, 948 F.2d 388 (7th Cir.

1991). At 390-91:

Denying a pre-trial detainee access to

a telephone for four days would

violate the Constitution in certain

circumstances. The Sixth Amendment

right to counsel would be implicated if

plaintiffwas not allowed to talk to his

lawyer for the entire four-day

period.... In addition, unreasonable

restrictions on prisoner's [sic]

telephone access may also violate the

First and Fourteenth Amendments.

Deliberate nontreatment of broken ribs and

hand for nine months presents a clear Eighth

Amendment violation. The plaintiff is unable

to investigate personally because he is in a

different facility from the one in which the

claim arose. The case will involve conflicting

medical evidence. For these reasons, counsel

should be appointed on remand.

Searches-Person-Visitors

and Staff

Cochrane v. Quattrochi, 949 F.2d 11 (lst

Cir. 1991). Strip searches of visitors must

be justified by "some as-yet undefined 'level

of individualized suspicion. ", (Citation

omitted.) The plaintiff was subjected to a

strip search when visiting her father,

allegedly because a confidential informant

had indicated that she had smuggled in

drugs. The plaintiff's father had previously

accused the defendant of providing him with

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

drugs and the defendant had allegedly

responded, "I'm going to get you for that."

Adirected verdict for the defendant after

the plaintiff's case was improper. A

reasonable jury could have found that the

strip search was conducted in retaliation for

the plaintiff's father's allegations, and

therefore without individualized suspicion,

based on the plaintiff's testimony plus the

defendant's testimony that he could not

remember the name of the informant until

the morning of the trial, and the fact that he

vouched for the informant's credibility only

in general terms.

Procedural Due Process-Property

Freeman v. Dept. ofCorrections, 949

F.2d 360 (10th Cir. 1991). The plaintiff

alleged that prison officials confiscated his

stereo and refused to return it, his administrative grievances were unsuccessful, and

the small claims court never responded to

his suit despite repeated inquiries. Subsequently, prison officials induced him to

drop his suit by promising to give him his

stereo back, but did not do so.

The plaintiff's due process claim should not

have been dismissed as frivolous. He set forth

"specific facts suggesting that the state postdeprivation remedies were effectively denied

to him." (362) The existence of a statutory

remedy may create a presumption of adequate

due process, but it is not conclusive.

Personal PropertylReligionl

Appointment of CounsellEqual

ProtectionlProcedural Due Process

Abdullah v. Gunter, 949 F.2d 1032 (8th

Cir. 1991). The plaintiff tried to donate $2

to a mosque in Lincoln, Nebraska, and

prison officials forbade the donation

pursuant to policy.

The district court should have appointed

counsel. Once the court determines that a

claim is neither frivolous nor malicious, the

court must determine the plaintiff's need for

counsel and-the benefit to plaintiff and the

court from the assistance of counsel. This

inquiry is governed by "the factual complexity of the case, the ability of the indigent to

investigate the facts, the existence of

conflicting testimony, the ability of the

indigent to present his claim and the

complexity of the legal issues." (1035,

citation omitted.) The plaintiff had the

burden of showing that the policy was not

reasonably related to legitimate penological

interests. Since there were genuine issues of

material fact as to some of the Turner

factors, the case was both legally and

factually complex. The plaintiff lacked

sufficient resources to investigate the

relevant facts, e.g., "the extent to which the

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

prison policy actually controlled the flow of

inmate funds and illegal activities, the

impact of permitting Zakah on the prison

system, and the existence or absence of

ready alternatives to the regulation." (1036)

The fact that the case was to be tried to a

jury also supported the appointment of

counsel.

Use of ForcelDiscovery/.~

Appointment of Counsel

,

),.(

Murphy v. Kellar, 950 F.2d 290 (5tn;Cir.

1992). The plaintiff alleged that as a result

of his filing of grievances he was beaten and

otherwise abused. The district court

dismissed because he could not sufficiently

identify the defendants. However, he

prOVided some identifying information and

explained that he could not do better

because they were not wearing their name

tags and because he was punished for his

efforts to identify them more fully. The .

district court is directed to allow him to

conduct discovery, e.g., of duty rosters and

personnel records.

The district court is also directed to

consider appointing counsel based on the

fact that "Murphy is a prisoner and those he

is trying to identify are prison officials" and

"competent discovery would allow the court

to efficiently and conclusively determine

whether Murphy is able to adequately

identify his alleged attackers.... "

Medical Care/Damages/Jury

Instructions and Special Verdicts

Warren v. Fanning, 950 F.2d 1370 (8th

Cir. 1991). The plaintiff complained for a

year about a foot problem before the

prison'S contract physician sent him to a

specialist, who rendered a different

diagnosis and provided different treatment.

The contract physician's trial testimony

"reveals an attitude towards Warren's

medical needs that reasonably could be

viewed as indifferent, if not contemptuous."

(1373) Ajury verdict finding an Eighth

Amendment violation is therefore upheld.

Ex Post Facto Laws/Good Time

Arnold v. Cody, 951 F.2d 280 (10th Cir.

1991). The plaintiff was provided with

"emergency time credits" under the

Oklahoma Prison Overcrowding Emergency

Powers Act in effect at the time of his

offense. He was then deprived of them by

subsequent statutory amendment which

denied those credits to persons who have

been denied parole. These emergency

credits would be applied only in the event of

a future overcrowding emergency.

The statutory amendment constituted an ex

postfacto law as applied to the plaintiff and

he was entitled to have his emergency credits

calculated as of the time of the offense.

Pre-Trial Detainees/Protection

from Inmate AssaultlDiscovery

Dean v. Barber, 951 F.2d 1210 (11th Cir.

1992). The district court should not have

granted summary judgment without first

ruling on the plaintiff's motion to compel

discovery, e.g., the production of the jail's

classification procedures and history of

violent incidents in the jail.

"

Law Librad~s and Law Books

" 951 F.2d 1504 (9th Cir.

Gluth v. Kangas,

1991). Since the defendants submitted no

evidence of the actual operation of their

policy, and the plaintiffs submitted unrebutted

evidence of unconstitutional conditions,

summary judgment was properly denied to the

defendants and granted to the plaintiffs.

Inmates denied physical access to the law

library are entitled to help from trained

legal assistants (n. 1). Defendants' failure to

establish any qualifications or provide any

training for legal assistants entitled the

plaintiffs to summary judgment. An injunction requiring training of inmate paralegals

was not an abuse of discretion.

Undisputed evidence of arbitrary denials

of, and restrictions on, law library access

entitled the plaintiffs to summary judgment.

At 1508: "It is the state's burden to provide

meaningful access and to demonstrate that

its chosen method is adequate."

Apolicy that "forces inmates to choose

between purchasing hygienic supplies and

essential legal supplies, is 'unacceptable. '"

(1508) Under the policy, inmates were

entitled to indigent status if they had less

than $12 in their accounts and their income

for the previous 30 days had not exceeded

$12. It cost at least $46 to purchase

necessary personal items and legal supplies

and inmates had to purchase hygiene items

in order to avoid punishment.

The district court did not abuse its

discretion in ordering an indigency

threshold of $46 and a minimum amount of

supplies for indigents. At 1510:

While the Constitution does not

require any particular number ofpens

or sheets ofpaper, it does require

some.... The district court acted within

its discretion when it concluded that

numerical minimums are the best way

to ensure that indigent inmates get the

required pens and paper.

Since the "core Bounds requirements"

are not involved in the indigency policy

claim, the plaintiffs were reqUired to prove

actual injury. At n. 2: This requirement was

met by their uncontroverted allegation that

SUMMER 1992 9

"[nl on-indigent inmates without funds have

cases that go unfiled or have been dismissed

due to the high cost of postage, legal copies,

and legal supplies."

Procedural Due ProcessVisiting/Crowding

Patchette v. Nix, 952 F.2d 158 (8th Cir.

1991). Regulations providing for specific

visiting hours, combined with other

regulations providing that visiting procedures may be temporarily modified or

suspended under certain specified circumstances ("riot, disturbance, fire, labor

dispute, space restriction, natural disaster,

or other extreme emergency"), created a

liberty interest protected by due process.

The court does not say what process was

required in this case. Ordinarily, due

process reqUires procedures of some sort,

but the main concern of this opinion is

whether the substantive standards in the

regulation were followed.

Religion-Practices

McKinney V. Maynard, 952 F.2d 350 (lOth

Cir. 1991). The Native American plaintiff

alleged that he was denied his medicine bag,

required to cut his hair, denied an exemption

from the grooming code, and denied the

right to build a sweat lodge. His claim

should not have been dismissed as frivolous,

since prisoners were permitted to possess

artifacts of other religions, and since the

plaintiff alleged he was denied all means of

religious expression.

Crowding/Summary Judgment

Williams v. Griffin, 952 F.2d 820 (4th

Cir. 1991). The plaintiff's verified complaint, which described allegedly unconstitutional prison conditions, was based on

personal knowledge, and set forth specific

admissible facts, should have been considered in response to defendants' summary

judgment motion.

At 824-25: ...

is clear that double or triple ceiling

ofinmates is not per se unconstitutional... But, overcrowding accompanied by unsanitary and

dangerous conditions can constitute

an Eighth Amendment violation,

provided an identifiable human need

is being deprived.

Allegations of crowding combined with

unsanitary conditions, insufficient showers,

flooding with sewage from leaking toilets,

deprivation of blankets and coats, and

infestation of insects and vermin raised a

genUine factual issue under the Eighth

Amendment.

The plaintiff's failure to allege harm

It

10 SUMMER 1992

resulting from the crowded and unsanitary

conditions did not reqUire dismissal of his

complaint. At 825: "It seems apparent that

psychological harm could be inferred,... , as

could an increased likelihood of illness and

violence."

,

Evidence that prison officials had been

placed on notice of unlawful conditions

supported a finding of deliberate indiffer- :.;ence. At 826: "... [0 1nee prison officials

become aware of a problem with prison i:,;

conditions, they cannot simply ignore the /~

problem, but should take corrective action

when warranted." The evidence consisted of

published reports concerning prison

conditions, grievances that the plaintiff and

other prisoners had allegedly filed, and

inspection reports.

Pre-Trial Detainees/Medical CareStandards of Liability-Serious

Medical Needs

Johnson V. Busby, 953 F.2d 349 (8th Cir.

1991). The district court properly instructed the jury that a serious medical need

is "one that has been diagnosed by a

physician as requiring treatment, or one that

is so obvious that even a lay person would

easily recognize the necessity for a doctor's

attention." (351)

Procedural Due ProcessAdministrative Segregation

Layton V. Beyer, 953 F.2d 839 (3d Cir.

1992). New Jersey regulations create a liberty

interest in staying out of the "Management

Control Unit" (administrative segregation). At

847: "...the inmate has a reasonable expectation that if he never poses a threat to others,

to property, or to the operation of a facility,

he will remain free of the restrictive confinement of M.C.U. and Prehearing M.C.U." The

court views Kentucky Dept. ofCorrections V.

Thompson as holding that regulations must

eliminate any discretion to apply criteria

other than the regulations' substantive

predicates. It rejects the view that under

Thompson, "the official action must be

mandated whenever the relevant substantive

criteria have been met" (848) (emphasis in

original). This interpretation reconciles

Thompson and Hewitt V. Helms.

Use of ForcelTraining

Russo V. City ofCincinnati, 953 F.2d

1036 (6th Cir. 1992). Evidence that officers

admitted they were frequently called on to

deal with mentally and emotionally disturbed and disabled persons, but that they

could not remember their training on that

subject, combined with expert testimony as

to the adequacy of their training, raised a

factual issue precluding summary judgment

concerning the adequacy of the municipality's training.

Recreation and Exercise/

Qualified Immunity

Mitchell V. Rice, 954 F.2d 187 (4th Cir.

1992). The plaintiff, who had an extensive

and continuing record of assaultive behaVior

and had already been placed in "maximum

custody assigned to intensive management,"

was subjected to 32 months of arm and leg

restraints whenever he left his cell, and was

denied any out-of-'ell recreation or exercise

for 18 of them..' ~~~

The defendants were not entitled to

qualified immunity on this record. It was

established that though denial of out-of-cell

exercise is not per se cruel and unusual,

"generally a prisoner should be permitted

some regular out-of-cell exercise." (l91,

footnote omitted.) At 192: "It seems proper

to require a...showing of infeasibility of

alternatives, excepting financial justifications, before granting qualified immunity."

The plaintiff's unmanageable, violent nature

may present sufficiently exceptional

circumstances to justify the deprivation. At

193: "A detailed review of the feasibility of

alternatives in this case, such as solitary

out-of-cell exercise periods, or the adequacy of in-cell exercise would need to

precede a grant of qualified immunity in a

case such as this."

MunicipalitieslFalse Imprisonment!

Procedural Due Process

Oviatt by and through Waugh V. Pearce,

954 F.2d 1470 (9th Cir. 1992). The

schizophrenic plaintiff waited four months

for arraignment because of a court clerk's

error. Ajury awarded him $65,000 on his

constitutional and tort claims.

Freedom from unjustified incarceration is

a constitutionally based liberty interest. In

addition, liberty interests were created by

state statutes reqUiring release after 60 days

if no trial has been held and requiring

arraignment within 36 hours absent good

cause. Under Mathews V. Eldridge, the

sheriff's failure to provide an internal

procedure for keeping track of whether

inmates had been arraigned or otherwise

appeared in court was unconstitutional.

DISTRICT COURTS

Women/Equal Protection

McCoy V. Nevada Dept. ofPrisons, 776

F.Supp. 521 (D.Nev. 1991). Prison gender

discrimination cases are governed by the

"heightened standard" that permits

discrimination only if it serves important

governmental objectives and is substantially

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

related to achieving them. Female prisoners

must be treated "in parity" with male

prisoners (523). The Turner reasonable

relationship test does not apply (n. 2).

Evidence that male inmates had access to a

wider variety of educational and vocational

training programs, better recreation programs and more facilities per capita, more

privileges in connection with visiting, more

lock-out time, unmonitored telephones, better

visiting conditions, more ice machines,

better law libraries, better commissary

services, better building maintenance and

more clothing, barred summary judgment

for the defendants. Summary judgment is

granted as to various other claims as to

which the plaintiffs submitted no evidence of

disparate treatment.

I

AIDS/State Law in Federal Courts/

Privacy/Deference

Nolley v. County ofErie, 776 F.Supp. 715

(W.D.N.Y. 1991). Jail officials placed a red

sticker on the jail medical and transportation record of the HlV-positive plaintiff,

placed her in a unit for the mentally

disturbed and sUicidal, and barred her from

the law library and religious services.

There is a private cause of action under

state statutes protecting the confidentiality

of HlV-related information. The red sticker

policy violated the statute and the regulations promulgated under it.

The constitutional right to privacy

"includes protection against unwarranted

disclosure of one's medical records or

condition." (729) Prisoner privacy claims

are governed by the Turner reasonable

relationship standard. The red sticker policy

is not reasonably related to protecting staff

from infection because it is underinclusive,

Le., there are clearly inmates who are

infected but not known to be infected. There

is a readily available (and superior)

alternative-using universal precautions.

Since universal precautions had later been

instituted, there would be minimal impact

on staff and others.

The plaintiff's segregation violated the

state statute. It also was unreasonable under

Turner because it was so "remotely

connected" to legitimate goals. It is a

prisoner's behavior, not the mere fact of

HIV infection, that makes transmission

likely. In addition, the segregation was

contrary to the jail's own policy, rendering

it an "exaggerated response." (736)

The plaintiff's segregation denied due

process. It is more analogous to placement

in a mental hospital than to security-related

segregation because it involved a stigma

similar to mental hospital confinement. The

deranged behavior of the other inmates

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEG JOURNAL

rendered confinement with them "qualitatively different from the punishment

normally suffered by a person convicted of a

crime." (738) In addition, the plaintiff's

confinement was indefinite and not subject

to periodic review. Jail regulations provid-,

ing for mandatory review "to determine ':1:

whether the reasons for initial placement 1ff'

the unit still exist" and stating that housing

decisions will not be made solely on the." .

basis of HlV status created a liberty int~~est

in staying in general population.

,';;

The plaintiff's exclusion from the law

library, denial of face-to-face access to inmate

law clerks, and relegation to a copying system

that required her to identify specific materials

for copying denied access to courts. At 741:

"By now choosing to alter these practices,

defendants have essentially admitted that the

prior practice was misguided." The practice

also was unreasonable under the Turner test.

The plaintiff's exclusion from religious

services violated the First Amendment.

Use of Force/Administrative

Segregation-High Security

Friends v. Moore, 776 F.Supp. 1382

(E.D.Mo. 1991). The plaintiff suffered a

bloody nose as a result of being subdued in

his cell by a "movement team" because he

would not give up his clothing to be put in a

strip cell. The use of force did not violate

the Eighth Amendment.

The plaintiff was also stripped and left

naked and wet in an outdoor recreation area

for less than two hours. The Eighth Amendment was not violated because the defendants did not intend to punish but only to

restore order and to clean up the plaintiff's

cell, which he had flooded. There was no

evidence that he was cold or in discomfort

(even though a video-tape showed him

pacing "like a caged lion").

This opinion is notable for its depiction of

mutually abusive behavior by staff and

inmates in a high-security unit. It also notes

that an officer was assigned to examine the

plaintiff's feces for a missing handcuff key.

It is also another case in which the video

camera somehow malfunctioned at the point

when the incident started.

Medical Care/Injunctive Relief

McCargo v. Vaughn, 778 F.Supp. 1341

(E.D.Pa. 1991). The court had previously

issued a preliminary injunction requiring

prison officials to establish a system for

diabetic inmates to receive special diets and

to assure them access to insulin. It then

ordered that the injunction be made

permanent, and the defendants moved to

alter or amend on the ground that it provided relief to persons who were nonparties.

An injunction can benefit persons who are

nonparties to the litigation even if no class

has been certified. At 1342: "Where as here

an injunction is warranted by a finding of

defendants' outrageous unlawful practices,

the injunction is not prohibited merely

because it confers benefits upon individuals

who were not named plaintiffs or members

of a formally certified class."

Protection from Inmate Assault

Smith v. Artison, 779 F.Supp. 113

(E.D.Wis. 1991'. An allegation that the

plaintiff warne~the sheriff about threats of

assault he had received from other inmates,

the sheriff disregarded the warnings, and

the plaintiff was subsequently assaulted was

not frivolous under the deliberate indifference standard.

Procedural Due ProcessVisiting/Qualified Immunity

Van Poyck v. Dugger, 779 F.Supp. 571

(M.D.Fla. 1991). Prison officials denied

visiting rights to the fiancee of the plaintiff, a

death row inmate, because she had worked

for six months as a nurse in a jail and her

knowledge of jail operations allegedly made

her a security risk. The plaintiff alleged that .

he was being retaliated against because he

had murdered a correctional officer and

because of his legal activities.

There is no absolute right to visit, and the

denial of access to a particular visitor is not

protected by the due process clause unless

state law creates a liberty interest. Florida

visiting regulations create such an interest.

They provide substantive predicates (an

exhaustive list of reasons permitting denial of

visits from particular persons) and mandatory

language ("shall" all over the place).

The defendants are not entitled to

qualified immunity because it is clearly

established that it is unlawful to deny an

inmate visiting privileges without legitimate

penological objectives.

AccidentslNegligence, Deliberate

Indifference and Intent

Choate v. Lockhart, 779 F.Supp. 987

(E.D.Ark. 1991). The defendant prison

officials "demonstrated reckless disregard

for plaintiff's safety when he was directed to

perform work on a 45 degree angle plywood

roof, without toe boards or scaffoldings

installed, when plaintiff, among other things

possessed a recognizable infirm right leg."

(988) The defendants included the director

of the Arkansas Department of Correction,

for whose personal use a garage was being

constructed. Inmates had complained about

the working conditions and had been told to

"shut up and go back to work."

SUMMER 1992 11

Protection from Inmate Assault!

Color of Law

Payne v. Monroe County, 779 F.Supp.

1330 (S.D.Fla. 1991). The county government could not be held liable for an inmate

assault because there was no evidence that it

knew or should have known that the

assailant would attack the plaintiff. The

court ignores the plaintiff's allegation that

crowding created an unreasonable risk of

assault, focusing instead on the risk to him

from the particular assailant.

The Wackenhut Corporation acted under

color of state law since it "was authorized to

exercise supervision and control over the

functions of the Monroe County JaiL"

(1335) The claim against it is dismissed

because of the lack of allegations of

deliberate indifference.

Law Libraries and Law Books/

Pre-Trial Detainees

Kaiser v. County ofSacramento, 780

F.Supp. 1309 (E.D.Cal. 1991). The county

policy with respect to pre-trial detainees

representing themselves was to provide a

"pro per" information package, copies of

the appropriate statutory sections, information packets pertaining to various motions,

habeas corpus, §1983 actions and other

matters, plus a cell delivery system for law

books permitting generalized requests for

books in a certain area (with a one-day

turnaround for persons defending themselves), and Shepardizing. The plaintiffs

submitted evidence that the system "work[s]

more poorly in practice" than in theory, but

the court finds that it satisfies their Sixth

Amendment rights for purposes of the

application for a preliminary injunction.

Further evidence of the system's failure

might justify a permanent injunction.

For convicted inmates, to whom Bounds

clearly applies, a paging system by itself is

clearly unconstitutional. While paging plus

legal assistance may satisfy Bounds, the

defendants' "assrstance"-obtaining general

references, narrowing the scope of legal

inquiries, and prOViding compiled packages

of forms and legal materials-may not meet

the standard. The court denies broad

preliminary relief because the plaintiffs have

not shown the extent of the harm to the

plaintiff class and have not proposed a

remedy with practical specifics. However, it

orders the posting of a complete list of

available legal reference materials.

Pro Se Litigation

Patrick v. Staples, 780 F.Supp. 1528

(N.D.Ind. 1991). At 1532:

As this massive Report and Recommendation clearly indicate, the disposition

12 SUMMER 1992

and management of pro se prisoner

to a pro se case.

litigation is just plain hard, timeDefendants were not entitled to summary

consuming work. The sooner that those

judgment on plaintiff's allegations that he

who record time consumption probwas subjected to involuntary psychotropic

abilities to such cases learn that lesson

medication while in jail. An affidavit alleging

the better all ofus in the federal trial

that the plaintiff was a "disciplinary

judiciary will be.

f nightmare" and that the drugs were

Intentional refusal to let the plaintiff see a

'~ administered by a "qualified medical aide

doctor when he was obviously sick stated an ;; following the orders of the facility's

Eighth Amendment claim.

. psychiatrist" was insufficient. Washington v.

Allegations that the plaintiff was not~;

Harper requires that the prisoner have "a

permitted to obtain his medication on one ~

serious mental illness" and be "dangerous

stated an Eighth Amendment claim; if the

to himself or other\," and that the treatment

defendant "deliberately interfered with his

be "in the inmate'~,imedical interest." (957)

medically prescribed treatment for the

It also provides fOr procedural requirepurpose of causing him unnecessary pain, she

ments, which are not addressed at all on

could be subject to liability even though he

this record.

suffered no apparent injury."

Good TimelHabeas Corpus

Allegations that the plaintiff was assigned to

Doughty v. U.S. Board ofParole, 782

a job or denied medical care because of his

F.Supp. 653 (D.D.C. 1992). The District of

race stated an equal protection claim. Other

Columbia Good Time Credits Act has been

such allegations, unsupported by any specific

amended to award credits to D.C. offenders

factual allegation demonstrating racial

animus, did not state an equal protection

housed in federal prisons outside the District.

The plaintiff would not be required to

claim. (1548)

exhaust his administrative remedies with

respect to deprivation of good time, since the

AIDSlPrivacy

defendants had declared uneqUivocally in

Lipinski v. Skinner, 781 F.Supp. 131

(N.D.N.Y. 1991). The plaintiff was arrested,

open court that they would not give him any

tested for HIV infection without his consent,

good time back.

The plaintiff's claim concerning good time

and jailed; his positive test results were

should have been brought as a habeas

disclosed by the doctor to the State Police,

corpus petition in the district where he was

who had asked for the test, and by them to

held and not as a suit for declaratory and

jail authorities. The information then

showed up in the local newspaper, allegedly

injunctive relief. Preiser is cited by analogy.

The court rejects the "creative" argument

because jail staff disclosed it.

that as a D.C offender the plaintiff is in the

The newspaper's editorial writer was not

custody of the Attorney General no matter

entitled under the First Amendment to

where he is incarcerated.

"absolute immunity" from discovery. The

newspaper's journalists, but not its editors,

were entitled to "qualified immunity."

Procedural Due Process-Disciplinary Proceedings/Summary Judgment

Discovery from the editors must be limited so

Russell v. Coughlin, 782 F.Supp. 876

as to minimize its impact on the journalists.

(S.D.N.Y. 1991). Incarcerated pro se litigants

Medical Care-Standards of

are entitled to notice of the consequences of

Liability-Deliberate Indifference

failure to respond to a summary judgment

motion. If they get it and still don't respond,

Diaz v. Broglin, 781 F.Supp. 566

the moving party is not automatically entitled

(N.D.Ind. 1991). At 574: "Although

negligence alone, or simple medical

to summary judgment; the court must

malpractice, is insufficient to state a claim

determine whether the facts set forth in the

for relief, ...courts have begun to recognize

moving party's statement of undisputed facts

warrant summary judgment.

that repeated, long-term negligent treatment

of a prisoner's medical condition, rather

Aprison official could not be held liable for

than intentional actions, may amount to

an unlawful disciplinary proceeding based on

deliberate indifference...." The plaintiff's

having appointed the hearing officers, absent

any evidence that he was involved in or aware

medical care claims are rejected for lack of

factual substantiation.

of their wrongful conduct or knew that one of

them had prior involvement with the case.

The hearing officer could not be held liable

Mental Health CarePsychotropic Drugs

for declining to call witnesses when he