Journal 6-1

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

>'

""j-f

A PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN CIVllliBERTlES UNION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOl. 6, NO.1, WINTER 1991 • ISSN 074$-2655

,

}.:.~,

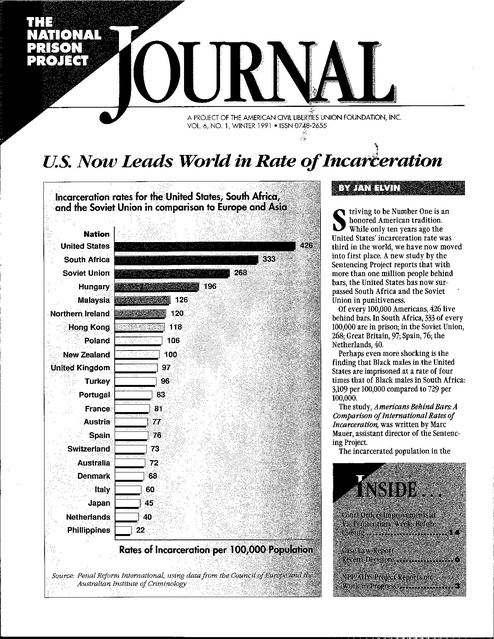

U.S. Now Leads World in Rate ofIncarieration

Incarceration rates for the United States, South Afric

and the Soviet Union in comparison to Europe an

Nation

United States

South Africa

Soviet Union

Hungary

Malaysia

Northern Ireland

Hong Kong

Poland

New Zealand

United Kingdom

Turkey

Portugal

France

81

Austria

77

Spain

76

Switzerland

73

Australia

72

Denmark

68

Italy

60

Japan

45

Netherlands

40

Phillippines

22

Source: Penal Reform International, using data from theCou· .

Australian Institute ofCriminology

triving to be Number One is an

honored American tradition.

While only ten years ago the

United States' incarceration rate was

third in the world, we have now moved

into first place. Anew study by the

Sentencing Project reports that with

more than one million people behind

bars, the United States has now surpassed South Africa and the Soviet

Union in punitiveness.

Of every 100,000 Americans, 426 live

behind bars. In South Africa, 333 of every

100,000 are in prison; in the Soviet Union,

268; Great Britain, 97; Spain, 76; the

Netherlands, 40.

Perhaps even more shocking is the

finding that Black males in the United

States are imprisoned at a rate of four

times that of Black males in South Africa:

3,109 per 100,000 compared to 729 per

100,000.

The study, Americans Behind Bars: A

Comparison ofInternational Rates of

Incarceration, was written by Marc

Mauer, assistant director of the Sentencing Project.

The incarcerated population in the

S

,

United States has more than doubled in

thelast decade, rising from just over

500,000 in 1980 to one million today. The

study stresses that incarceration rates,

however, do not rise and fall with crime

rates. "Although the crime rate has

dropped by 35% since 1980, the prison

population has doubled in that period," it

notes. "Breaking down these figures

further, we see first that crime dropped

by 15% from 1980 to 1984, while the

number of prisoners increased by 41%;

then, from 1984-1989 crime rates climbed

by 14%, while the number of prisoners

rose by 52%. Any cause and effect

relationship is difficult to discern." The

statistics are furnished by the F.B.I..

Fear of crime and increasingly punitive

attitudes in recent years have led to

mandatory sentencing laws and tougher

sentencing guidelines. Mauer suggests

that these new laws reflect counterproductive and inappropriate policy choices.

"The choice for policy makers in responding to our high national crime rate...was

very stark. The first option was to

continue to build new prisons and jails at

a cost of $50,000 a cell or more, and to

spend $20,000 a year to house each

prisoner, or to spend these same tax

dollars on prevention policies and

services-programs designed to generate

employment and to provide quality

education, health care, and housing,

along with alternatives to incarceration

rather than new prison cells....

"Overwhelmingly, the punitive policies

of the first option were the ones selected

at both a national and local level," says

the report. "Had the punitive policies

resulted in dramatically reduced crime

rates, one could argue that their great

expense was partially justified by the

results. But as the 1990s begin, we are

faced with the same problems as in 19~f);

only greater in d e g r e e . " · p

The Sentencing Project recommends:' if

· repeal of mandatory sentencing laws;

· expansion of alternatives to incarceration;

· treatment of drug abuse as a health

problem rather than a criminal justice

problem;

· redirection of the focus of law

enforcement to address community needs

and to prevent crime;

· government funding of pilot programs to reduce the high rate of imprisonment of African American males; and

· establishment of a national commission to examine the high rate of incarceration of Americans, particularly

African American males.

Copies of the report are available from

The Sentencing Project, 918 FSt., NW,

Washington, D.C. 20004 for $5.•

To the Editor:

I appreciate the use of our article in

your story by Russ Immarigeon on

alternatives to capital punishment,

2 WINTER 1991

Alvin J. Bronstein, Executive Director

The National Prison Project of the

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

1875 Connectic~ Ave., NW, #410

Washington, D.q. 20009

(202) 234-483P-' FAX (202) 234-4890

The National Prison Proied is a tax~exempt foundationfunded project of the ACLU Foundation which seeks to

strengthen and protect the rights of adult and iuvenile

offenders; to improve overall conditions in correctional

facilities by using existing administrative, legislative and

judicial channels; and to develop alternatives to

incarceration.

The reprinting of JOURNAL material is encouroged with

the stipulation that the National Prison Project JOURNAL

be cnedited with the reprint, and that a copy of the reprint

be sent to the editor.

The JOURNAL is scheduled for publication quarterly by

the National Prison Project. Materials and suggestions

are welcome.

The NPPJOURNAL isavailable on16mm

microfilm, 35mm microfilm and 105mm

microfiche from University Microfilms

International, 300 North Zeeb Rd., Ann

Arbor, MI 48106-1346.

jan Elvin is editor Of the NPPJOURNAL.

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

In his article in the Summer 1990 issue

of the NPPJOURNAL, Russ Immarigeon

discussed alternativepunishments to the

death penalty, noting that anti-death

penalty efforts which fail to suggest

alternatives are incomplete.J The most

popular alternative, life withoutparole,

he wrote, was an unsatisfactorily broad

political ameliorative." Drawingfrom

recent studies and surveys, he instead

proposed alternatives such as increased

victim servicesprograms, the

demystification of violence through

education, broader use ofdefense-based

sentencing advocacy services, and

penalties which coordinate safety and

victims' needs with social services and

treatment. Two death penalty opponents

respond to his article in the following

letters.

Editor: Jan Elvin

Editorial Asst.: Betsy Bernat

"Instead of Death: Alternatives to Capital

Punishment," Vo15, No.3 (Summer 1990),

although its publication year was not

1990, but rather 1989.

The difficulty I have is that Mr.

Immarigeon evidently fails to recognize

that... one need not affirmatively

advocate life without parole ("L WOP") in

order to take advantage of the public's

preference for some version of LWOP as

an alternative to the death penalty.

Instead, one can point out (as the article

does at the outset) the fact thatwhether we like it or not-LWOP does

already exist in most jurisdictions, and

hence the assertion that the death

penalty is needed to incapacitate death

row inmates from being released speedily

to kill again is simply untrue.

To me, that is the key point. It is a

factual point which does not require us

to come up with some other theoretical

alternative to the death penalty now.

What's crucial is to explain that an

alternative that is preferable to the

public already exists. Once the public

knows that, many fewer sentences of

death will be imposed, and we may be

able to abolish capital punishment.

Thereafter, we can come up with the

other sorts of alternatives hypothesized

by Mr. Immarigeon.

Ronald J. Tabak, Esq.

Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom,

New York

To the Editor:

As a matter of prUdence, Mr.

Immarigeon is right in suggesting that

we need to propose alternatives to the

death penalty, but only as a matter of

political prudence. Those who advocated

the end of burning at the stake or

drawing and quartering were hardly

obligated, morally, on the merits, to offer

alternatives to calm society's shattered

nerves.

But so long as it is prudent, I am not

sure his catalogue is terribly persuasive.

The four he propounds-victim services,

demystifying Violence, sentencing

advocacy, and new kinds of penalties

(largely non-incarcerative, I suppose)THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

i

rl

all have merits quite unrelated to the

retention vel non of the death penalty

and they seem to me utterly unlikely to

appease the public's desire for tough

retributiveness (to say nothing of the

courts'). They not only do not address the

problem, they dis-address it, if I may say

so, by more "liberal" social service

techniques whose failure (or at least

perceived failures) are precisely what

has turned the society so anti-liberal. No

one trusts you to cure child abuse before

they get stabbed waiting for the evening

bus; that's what it amounts to. Indeed, if

you got those four programs actively

implemented, they could serenely coexist with capital punishment (and

probably would).

I abhor life-without-parole notions as

does Mr. Immarigeon. I understand the

Governor's felt political need for that

push in New York, but I will not be heard

to endorse it. Leon Sheleff (in his

Ultimate Penalties) quite unnecessarily

reproaches the American abolition

movement for surreptitiously supporting

LWOP to slake the public's thirst for

beastliness.

Henry Schwarzschild, Director

ACLU Capital Punishment Project,

NewYork

To the Editor:

I really appreciated David Fathi's

article on U.S. political dissent in your:f

Fall 1990 issue? but he made a small but

significant historical error when h~;~'

states that Congress in 1940 enacted~he

Smith Act to "criminalize membershfp in

the Communist Party." Actually the

Communist Party favored the passage of

the Smith Act because it supported World

War II and the Act originally targeted

anti-war Trotskyists. It is both one of the

great ironies of the left and one of the

best historical arguments for civil

liberties for all regardless of political

belief that the CP originally endorsed an

act that after the war would have such a

devastating impact on it.

Bill Douglas, Director

Criminal Justice Ministries, Des Moines

AIDS Project Presses for

Programs Behind Walls

ince the beginning of the AIDS

epidemic, there have been 5,411

cases of full-blown AIDS in jails and

prisons. This figure represents a conservative estimate because many AIDS cases

are still misdiagnosed or unreported.

Statistics compiled for 1989 show, for the

first time, that the percentage increase of

AIDS cases in prisons

and jails exceeded the

increase in the outside

general population;

prison and jail AIDS

cases in the United

States increased by

72%, while cases on

the outside only

increased by 50%. To

some extent, the

higher percentage in

prison AIDS cases

reflects better

reporting measures, more accurate

testing and better record keeping than

the previous year. However, it also

highlights the changing nature of the

HIV epidemic in this country. The spread

of HIV disease in the United States has

shifted from the white gay male popula-

S

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

tion to poor communities heavily

affected by IV drug use and addiction. In

particular, Black and Latino populations

are increasingly at risk. Because Blacks

and Latinos are disproportionately

represented in our nation's jails and

prisons, the number of prisoners with

HIV disease has grown. Notably, however,

the growth in the

number of HIVinfected in jails and

prisons is not due to

transmission within

the institutions.

Instead, people are

coming into prisons

from the street

already infected.

Today's profile of a

prisoner with HIV

disease is a Black or

Latino male with a

history of IV drug use. While the percentage of women with AIDS in prison has

been increasing rapidly, women still

comprise less than 10% of that population.

Most correctional AIDS cases are still

found in the Mid-Atlantic states of New

York and New Jersey (over 60%).

Fathi replies. While I wholeheartedly

agree with Bill Douglas on the importance of resisting repressive legislation,

whoever the ostensible target, he is

incorrect when he states that the

Communist Party originally supported

the Smith Act. The origin of this persistent misconception is unknown, although it has been attributed to Socialist

Party leader Norman Thomas. In fact, the

CP vigorously fought the Smith Act from

its inception, and several party leaders,

notably Eliza~eth Gurley Flynn, actively

opposed the Stnith Act prosecution of

Trotskyists: Ail account of these events

may be found in Herbert Aptheker, Can

We Be Free? An Analysis of the Smith/

McCarran Act~ published at the height

of the Smith Act trials.

1 "Instead of Death: Alternatives to the

Death Penalty," NPPJOURNAL, Vo15, No.3.

2 "U.S. Punishes Political Dissidents," NPP

JOURNAL, Vo15, No.4.

These data present both a challenge .

and an opportunity for public health

officials and prisoner advocates. Traditionally, IV drug users have been a very

difficult population to educate about the

AIDS epidemic, but imprisonment offers

a prime opportunity to reach them. At

the same time, public health and prisoner

advocates have encountered formidable

obstacles in putting together AIDS

programs.

This past year the AIDS Project of the

National Prison Project has encouraged

the development of effective AIDS

education programs targeted to the

special needs and concerns of prisoners.

Much of our work reflects an effort to

encourage corrections administrators,

medical service directors, AIDS service

organizations, state legislatures, and AIDS

activists to provide quality, comprehensive AIDS education to prisoners and

staff. Also, we have stepped up our

support for peer education and counseling efforts in the jails and prisons

because health educators on the outside

have emphasized the importance of

organizing community-run AIDS

education programs.

Last December, for example, Judy

Greenspan, AIDS information coordinator for the Project, attended AIDS

education seminars at Rikers Island,

which is part of the New York City jail

system. While there, she interviewed

staff at the Center for Community Action

WINTER 1991 3

r

to Prevent AIDS at Hunter College. The

Center has been in the forefront of

developing peer education and counseling projects in poor communities in New

York City. The Center recently initiated

an "empowerment" AIDS education

project for women prisoners at Rikers

Island. Greenspan interviewed Dr.

Nicholas Freudenberg, the director of the

Hunter College Center for Community

Action and author of the book Preventing AIDS, A Guide to Effective Education

for the Prevention ofHIV Infection.

In March 1990 the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AmFAR) invited

NPP staff to serve on their Expert Review

Panel in the AIDS Education Material

Review Project, and to review a large

assortment of AIDS education materials.

In July, Ms. Greenspan attended a fourday Reviewer's Conference co-sponsored

by the National AIDS Information

Clearinghouse (NAIC) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease Control. We reviewed

over 1,600 brochures, videos, posters and

other AIDS information materials from

the NAIC database. We were able to meet

with a diverse group of AIDS and health

educators from around the country,

many of whom are beginning to do AIDS

education in local prisons.

The AIDS Project has lent assistance

over the past year to prisoner groups

who are developing peer education

programs at the Attica, Clinton, Eastern,

Fishkill, Great Meadow, and Bedford Hills

Correctional Facilities in New York State.

We have provided educational materials

and technical assistance to these pioneer

efforts. The Project also produces an

informal newsletter to prisoner AIDS

educators and counselors now being

circulated in several prisons in New York

State. Unfortunately, most New York

State prison administrators have not

responded favorably to prisonerdeveloped education programs.

Peer education efforts have met with

greater success in Massachusetts. An

ongoing, sanctioned AIDS education and

counseling program at MCI Norfolk has

received a great deal of support and

assistance from the AIDS Project.

One barrier that prisoner AIDS

educators constantly face is the lack of

support by outside AIDS service organizations for their efforts inside. The AIDS

Project has helped to form the Ad-Hoc

Prison Health Network-a broad group of

prisoner advocates, health educators,

people with AIDS and AIDS service

organizations, including the National

Lawyers' Guild AIDS Network,

4

WINTER 1991

ActionAIDS of Philadelphia, the nowdefunct National AIDS Network, and the

NPP. The first project of the Prison

Health Network was an all-day institute

held in Washington D.C. on July 18, 1990.

Over 100 health educators, attorneys and

others attended the day-long session

entitled "HIV/ AIDS Education and

Health Concerns for Incarcerated

Populations." Workshops were held on

medical and psychosocial issues, AIDS, ..

education for prisoners and staff, and ~"

advocacy and support for prisoners wHh

HIV disease.

Of course, the most valuable educational tool of the AIDS Project is the

brochure, AIDS & Prisons: The Factsfor

Inmates and Officers. This year, we

updated this educational tool to 27 pages,

with expanded sections on medical care

and legal rights for prisoners with AIDS.

We also added a new section on women

and AIDS. To date, we have distributed

135,000 copies in the prisons, jails, and

detention centers of this country. The

Spanish language pamphlet remains one

of the few resources available and

relevant to Latino prisoners.

In addition to education, another major

and continuing concern of the AIDS

Project has been to ensure that HIVinfected prisoners receive adequate

medical care and are treated fairly. Over

the past year, certain medical breakthroughs have led doctors to change

their views of this disease. AIDS, while

incurable, can be managed for an

increasing number of years as a chronic

condition rather than the "killer virus" it

was once considered. With proper

medical attention, frequent T4 cell

monitoring, and access to early treatment

regimens of such drugs as AZT and

aerosolized pentamidine, the life span of

people with HIV disease has increased

dramatically. The challenge for corrections, health educators and prisoner

advocates is to ensure that prison

medical care is upgraded to reflect

changes in treatment methods.

Despite the recent breakthroughs in the

treatment of HIV disease, most HIVpositive prisoners do not have access to

early or continuous medical care, even

though FDA-approved. Daily advocacy on

behalf of prisoners with HIV disease has

become one of the most important tasks of

the AIDS Project in the following ways:

· We respond to prisoners' requests by

mail and by phone;

· inform prison officials and prison

medical staff of the prisoners' complaints;

· provide medical information to

prisoners so they are better able to

monitor their own care;

. work with prison officials and

medical staff to improve their HIV

protocols; and

. obtain attorneys to represent the

prisoners if necessary.

Besides often being denied FDAapproved treatments, prisoners are

denied access to experimental HIV drug

trials. Last October, the AIDS Project

began collaborating with the AIDS

Action Foundat\pn to plan a roundtable

conference on prisoner access to experimental HIV dr,lf§ trials. Access to experimental drugs has been a life and death

issue for HIV-positive people in the

general population and a focus of AIDS

activists around the country. Prisoner

access to these drug trials is a much more

complicated and sensitive issue than is

access by people outside prison. After two

months of planning, this unique

roundtable conference, "Prisoner Access

to Experimental HIV Drug Trials," was

held in January 1990, in Washington, D.C.

An impressive grouping of medical

experts, ethicists, attorneys, people with

AIDS and health educators attended.

Since this roundtable meeting, prisoner

access to drug trials has been discussed

widely in both public policy and

corrections forums.

In addition to medical advocacy, the

AIDS Project is constantly called upon to

look at a range of problems stemming

from the isolation of HIV-positive

prisoners; the involuntary antibody

testing of prisoners; the lack of voluntary testing for prisoners; the lack of

confidentiality regarding medical records

and the identities of infected prisoners;

and the refusal of public officials to

develop early release policies for

prisoners dying of AIDS.

One of the most difficult aspects of this

work is finding lawyers who are willing

to represent HIV-infected prisoners. NPP

staff work hard to encourage prisoner

legal advocates across the country to

take on cases by contacting them and

offering support. We offer to assist

attorneys by tracking AIDS and prison

cases throughout the country. We help

them identify the issues and provide

referrals to experts in the field. Often

consultations continue throughout the

duration of a case.

Alexa Freeman, the AIDS Project

director, is writing the chapters on AIDS

and prison issues for the updated Yale

University Press book on AIDS and the

Law and the National Lawyers' Guild's

AIDS Litigation Manual The chapter in

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

the Litigation Manual is directed to

lawyers and should be helpful for those

considering taking these cases.

Most lawyers find the Project's updated

AIDS and Prison Bibliography very

useful. It remains in great demand with

over several hundred copies distributed

this past year. The 1990 Bibliography

contains one of the most comprehensive

legal case listings of AIDS and prison

issues. We have added an expanded

resource section listing educational

materials and organizations servicing a

variety of communities affected by the

AIDS epidemic.

Finally, Project advocacy on behalf of

HIV-infected prisoners has emphasized

public education. In the past year, staff

have provided background information

to news media and have been interviewed for stories on AIDS in prison. We

are frequently invited to speak at

conferences around the country. In the

past year these have included, among

others, the National Commission on

Correctional Health Care Conference, the

American Public Health Association

Conference, the Lavender Law Conference, a program on AIDS and the Bill of

Rights at Northern Virginia Community

College, the National Conference of Black

Lawyers Conference, and the ACLU

Executive Directors' and Lawyers'

Conference. Judy Greenspan continues to

write her AIDS Update column which

now appears regularly in the National

Prison Project JOURNAL.

Perhaps the most important public

education took place under the auspices

of the National Commission on AIDS

(formerly the Presidential Commission

on AIDS). The Commission held its first

hearing on AIDS and prison on August 17,

1990 in New York City. The AIDS Project

played a major role in the

conceptualization of this hearing and

helped develop the speakers' list. We

presented t@stimony on Harris v.

Thigpen, 727 F.Supp.1564 (M.D.Ala.1990),

a case brought by the National Prison

Project, the Southern Prisoners' Defense

Committee, and local lawyers challenging the mandatory HIV testing and

segregation of Alabama state prisoners,

and the inadequate medical and mental

health care provided them. We also

collected and presented testimony from

many prisoner peer educators and

prisoners with HIV disease to the

Commission. The Project is now advising

the Commission on the preparation of its

final report and recommendations to

President Bush.

The AIDS Project has embarked on

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

many exciting projects over the past

year. It is a unique national resource on

AIDS and prison issues and has played an

important role in encouraging local legal

advocates and AIDS service organizations

to tackle the complex problems faced by

prisoners with HIV disease and AIDS.

Project staff has its work cut out for it

over the next year: to continue to

advocate for comprehensive and

-,'

meaningful AIDS education programs for

incarcerated populations. Through ~he

Prison Health Network and our work

with local advocacy groups, the AIDS

Project will continue to seek to secure

sorely needed medical, psycho-social

support and legal services for prisoners

with HIV disease. At the same time, we

will continue to work with a growing

coalition of organizations, governmental

bodies like the National Commission on

AIDS, and individual corrections administrators, medical directors, health

educators, prisoners and AIDS activists to

develop model policies on the care and

management of HIV disease in the

nation's prisons and jails.•

Alexa P. Freeman, a staffattorney at

the NPp, is AlliSprojectdirector.

judy Greenspfm is the AIDS information

coordinator.

FOR THE RECORD

• The Summer 1990 issue of Jail

Suicide Update includes Part One of a

four-part series.on Model Jail Suicide

Prevention Programs.• The Update

describes a model program in the

Oneida, New York Correctional Facility

which relies on thorough Suicide

Prevention Screening Guidelines, three

levels of inmate supervision, and interagency cooperation involving local

mental health agencies. Jail Suicide

Updateis a quarterly newsletter

published by the National Center on

Institutions and Alternatives; the

Summer 1990 issue is available free to

readers of the NPPJOURNAL. Contact

the NationaFCenter on Institutions and

Alternatives, 40 Lantern Lane,

Mansfield, MA 02048,508/337-8806.

Jails which would like their model

suicide prevention program considered

foraJuture Jail Suicide Update

also contact NCIA.

.The Prison Fellowship has

announced it will officially launch

~merica's first national in-prison

newspaper,the Insidejournal, at the

DistrictCorrectionaFComplexat

Lorton, Virginia.

Writtenfor prisoners by current and

formerinmates, the premierissue of

the quarterly publication is being

distributed to prisons in Alabama,

California,Colorado, Connecticut,

Indiana, Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C. Future issues will be distributed to state and federal prisons

nationwide.

"Our primary goal is to provide

inmates with resources for life in prison

so that, once released, they will never

seHoot in prison again,"says Charles W.

Colson, Prison Fellowship chairman,

"With prisons packed to capacita'lld

national recidivism studiessho~i

that two out of three currentintnate~ '.

will return to prison, that'sata.IFQ~4e~

for a newspaper, but we believgl~$i e

journal is a step in the rightdire

Colson adds.

Former inmate and senior edit

Insidejourna~ Craig Pruit~addst~~t

"we want to introduce inmate

way of life, and at thesameti

with prison officials and thep

gaining a deeper understandin

justice system from the prison~

of view. We are delighted with

cooperation we've receivedfr()

correctional officials who've a

assist us in distributing then~

infederal and state prisons."

The newspaper will pUblis

stories ofcurrent andJorm.~r

and encourage them tocontri

its many columns, inclUding"

Behind the Walls" {news clip

prison life); "Bar None" (intIl

"Staying Together,"(advicea.

to inmates who will soon be

The Insidejournal alsowillf

professional sports schedules

on health issues that affec

entertainment, medicaFbreaK;

politics,and news from· other

institutions nationwide. Pruitt

the newspaper willprovideiIU

access to national statistics and

developing trends in prisons,t

resulting in more timelyresp()

solutions to prison problems.

For information,contactPrlso

Fellowship, P.O. Box 17500,Was

ton, D.C. 20041-0500, (703)834-3

WINTER 1991 5

A PROJEO OF THE AMERICAN CIVil LIBERTIES .UNION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOL 6, NO.1, WINTER 1991 • ISSN 0748-26,$

.e,:j~

Highlights of Most

Important Cases

Modification ofJudgments/Judicial

Disengagement

How long does a court injunction last? What

does it take for prison officials to get out from

under judicial supervision?

The Supreme Court's recent decision in

Board ofEducation of Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell, No. 89-1080 (U.S., January 15,

1991), a 30-year-old school desegregation case,

may make it easier for school officials to

escape the obligations of injunctive orders. But

Dowell's relevance to other civil rights

litigation, especially prison cases, is far from

clear, and in practice the decision may make

post-judgment monitoring in prison cases more

intrusive.

Traditionally, a defendant can escape the

obligations of an injunction only on a showing

of "grievous wrong evoked by new and

unforeseen conditions." United States v. SWift &

Co., 286 U.S. 106, 119 (1932).1 Dowellholds that

this is the wrong standard to apply to the

dissolution of school desegregation decrees. In

Swift an antitrust case, the decree "was by its

terms effective in perpetuity." By contrast,

"[f]rom the very first, federal supervision of

local school systems was intended as a

temporary measurl!'to remedy past discrimination." Therefore, the court held that a finding

that the schools were "being operated in

compliance with the commands of the Equal

Protection Clause, and that it was unlikely

that the school board would return to its

former ways," would suffice to justify

dissolving the decree.

The Dowell opinion, like most school desegregation cases, is framed almost entirely in

terms of desegregation law, without reference

to any general jurisprudence of civil rights

remedies. Its relevance to public institutions

other than schools is therefore debatable, and

there is good reason to believe it will have

little application to prison litigation.

6 WINTER 1991

Dowell dealt with classic de jure segrega~!e

tion, rooted in the state constitution and .,

statutes and buttressed by state-enforced

restrictive covenants and intentionally

discriminatory acts by the school board.

Racism is alive and well in America, but not

this kind of overt official discrimination. Jim

Crow has gone, and its days were obviously

numbered thirty years ago. It was entirely

reasonable to expect that school desegregation

decrees would be a "temporary measure to

remedy past desegregation," as even Justice

Marshall agreed in his dissenting opinion.

By contrast, the prison conditions that have

led to large-scale, protracted federal court

intervention are rarely archaic remnants of a

bygone social order. Rather, they arise from

lack of resources and administrative neglect

or incompetence, which in turn lead to

deteriorated physical facilities, correctional

and professional staffs that are inadequate

both in numbers and in qualifications,

administrative procedures that fail to deliver

essential services and to control hazards to life

and health, and the failure of lower-level

staff to carry out those policies and procedures that are nominally in place.

These problems are as modern as the

explosion in the prison population, competing

governmental priorities, and economic crises

in states and localities-none of which show

any sign of fading away within our lifetimes.

One need look no further than the case of

Tillery v. Owens, 719 FSupp.1256 (W.D. Pa.

1989), aff'd, 907 F.2d 418 (3d Cir.1990), to find

recent conditions comparable to those

described in the early large-scale prison

conditions cases in states like Alabama,

Mississippi, and Arkansas.

For these reasons, prisoners' advocates will

argue that prison conditions decrees are not

intended as temporary measures, but bear the

same expectations of permanency as any other

injunction. Constitutional compliance, they

will argue, is not evidence that the decree

should be vacated, but evidence that it is

safeguarding constitutional rights against the

ever-present dangers of overcrowding,

inadequate funding, and administrative

neglect. While enforcement mechanisms like

reporting requirements or the appointment of

a monitor may be limited in time, substantive

injunctive terms are presumptively permanent. See Battle v. Jtpderson, 788 F.2d 1421, 1428

(10th Cir.1986) (c~e dismissed but prior

orders and injunctions remained in force upon

a finding of no current constitutional

violation).

In many cases, these arguments will be

supported by the structure or language of the

decree itself. For example, if a decree contains

some provisions with explicit time limitations

and other provisions without them, plaintiffs

will plausibly argue that the latter provisions

were intended to operate indefinitely. This

argument should be particularly effective in

the case of negotiated judgments. See

Halderman v. PennhurstState School and

Hospital, 901 F.2d 311, 317-21 (3d Cir.1990), cert.

denied, 11l S.Ct. 140 (1990).

If Dowell does have some application to

prison cases-or as long as the question

remains open-post-judgment proceedings may

become more intrusive and formal, and good

will may be a casualty. The prudent plaintiffs'

lawyer will anticipate a motion to vacate

based on Dowelland will therefore closely

scrutinize defendants' performance for noncompliance and attempt to document in court

every manifestation of noncompliance, in

place of the present widespread practice of

resorting first to informal means of resolution.

Under Dowen therefore, post-judgment

practice may by necessity become more formal

and adversarial, and direct court involvement

may become more frequent.

Punitive Segregation

Once more, a federal court has found that

conditions in a punitive segregation unit

violated minimum standards of decency and

therefore constituted cruel and unusual

punishment. In LeMaire v. Maass, 745 F.Supp.

623 (D.Or.1990), the district judge condemned

the excessive use of physical restraints, the

punitive use of "controlled feeding status" and

"strip status," the denial of recreation to many

prisoners, and other aspects of confinement in

the Oregon State Penitentiary's Disciplinary

Segregation Unit (DSU).

The LeMaire opinion is striking for its

acknowledgment that the level of hostility

between staff and inmates in many segregation units is so great that staff misconduct, as

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEO JOURNAL

well as inmate misconduct, is not only possible

but is likely. The court observed:

Working under the constant threat of

unpredictable assaults and bombardment

with feces, urine, spiUood, and any available

movable object as DSUstaffdoes, is a

nightmare. It is understandable that in such

a hostile, violent and confrontational

environment inmates who are locked down

and isolatedfor almost 24 hours a day,

sometimesfor years on end, in tiny, damp,

smelly cells, with absolutely nothing to do, will

strike outany way they can. It is understandable thatguards will retaliate.

745 F.Supp. at 623.

This approach contrasts sharply with many

other prison conditions decisions, including

several by the Supreme Court, that have

emphasized the risk of dangerous misconduct

by prisoners but have ignored the equally real

risk of abuse of power by prison staff. See, e.g.,

Hudson v. Palmer, 468 U.S. 517 (1984) (holding

that prisoners have no Fourth Amendment

protection against abusive cell searches).

Restraints. Oregon regulations permit the

use of mechanical restraints in order to

control certain behavior, but require that the

re-straints be removed "as soon as it is

reasonable to believe that the behavior leading

to the use of restraints will not immediately

resume." Id. at 632 (quoting regulations). The

court found that in practice prisoners were left

in full mechanical restraints for days at a time

after acts of misconduct, without any

continuing emergency and without medical

justification. It observed: "Guards exposed to

constant abuse by inmates cannot be expected

always to make reasonable, controlled

judgments about the appropriate response to

inmate misbehavior." Id.

Food. Oregon regulations also permit serving

inmates meals of "Nutraloaf," which consists

of leftover foods ground up and baked into

bricks, when they throw or misuse food,

human waste, or utensils. Astate court had

previously upheld those regulations as facially

valid, and the federal court agreed that they

are a "valid, temporary safety measure when

[Nutraloaf's] use is directly connected to the

misconduct it is intended to curb." Id. at 633.

But it found that the use of Nutraloaf was far

more extensive; the record showed that

inmates were routinely kept on Nutraloaf

feeding for seven days regardless of whether

their disruptive behavior continued or

stopped, and some inmates were subjected to

Nutraloaf for misconduct that had little or

nothing to do with the misuse of food or

utensils. The court concluded that Nutraloaf

was being used as punishment, and that such

use violated the Eighth Amendment. The court

also concluded that by limiting the use of

Nutraloaf to particular purposes, and by

forbidding its use as punishment, state

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEG JOURNAL

regulations created a liberty interest. The use

of Nutraloaf as punishment therefore denied

due process. In reaching that conclusion, the

court observed once more that "in a hostile,

explosive environment, there is a high

likelihood of an erroneous deprivation." Id.

at 636.

",

Clothing, Furnishings, Property. The courq~

concluded that defendants' use of "strip">

status" was unconstitutional, for the same;;'

reasons it cited in connection with Nutraioaf

and mechanical restraints. Strip status C§»Sists

of the removal of all clothing, bedding,and

other property including toilet paper and

writing materials until such time as the

guards decide in their discretion that the

prisoner has "earned it back." Id. at 639.

Communication ofMedical Needs. The use

of "quiet cells" with double steel doors was

found unconstitutional. The court agreed that

it is legitimate to separate "noisy, disruptive

inmates" from the rest of the unit population,

but not to isolate them so completely from

staff that they cannot call for assistance in

the event of medical problems.

Exercise and Recreation. The imposition of

long periods of "loss of exercise privileges,"

resulting in segregation inmates being out of

their cells three times a week for showers

only, deprived the plaintiff of "outdoor

exposure and exercise opportunities adequate

to prevent physical and mental deterioration."

Id. at 643. The plaintiff had accumulated

almost four years of this punishment.

An injunctive judgement was entered in

January 1991, and prison officials have filed a

notice of appeal.

Environment-Hazardous

Substances and Conditions

Several federal courts have addressed the

constitutionality of subjecting prisoners to

"second-hand" cigarette smoke. Most recently,

a three-judge panel of the federal court of

appeals for the Tenth Circuit has held that a

policy of "permitting the indefinite doubleceiling of smokers with nonsmokers against

their expressed will can amount to deliberate

indifference to the health of nonsmoking

inmates...." Clemmons v. Bohannon, 918 F.2d

858 (10th Cir. 1990). By contrast, other federal

courts have held that subjection to secondhand smoke does not violate "evolving standards of decency" at the present time, though it

may in the future. Wilson v. Lynaugh, 878 F.2d

846,851-52 (5th Cir.1989), cert. denied, 110 S.Ct.

417 (1990); Caldwell v. Quinlan, 729 F.Supp. 4

(D.D.C.1990); Gorman v. Moody, 710 F.Supp.

1256,1259-64 (N.D.Ind.1989).

The Tenth Circuit did not merely disagree

with the outcomes of the other cited cases. It

accused them of asking the wrong question in

their Eighth Amendment analysis:

The dispute among these courts has centered

on the necessary extent ofpublic recognition

that long term exposure to ETS[environmental tobacco smoke] in close quarters is

potentially damaging to one's health, and how

much this recognition mustpercolate

throughout our social institutions and

become manifest in legislative enactments

before a court may invoke the "evolving

standards ofdecency that mark the progress

Ofa maturing society." We believe this type of

inquiry is unnecessary. The extensive line of

cases recognizing a prisoner's constitutional

right to a "healthy habilitative environment~ ..

reflects a longs'&ndingjudicial recognition

that exposing '4:~risoner to an unreasonable

risk ofa debilitating or terminal disease does

indeed offend these "evolving standards of

decency. "[Citations omitted.]

Thus, the question for the court is whether

infacta challenged practice "poses an

unreasonable risk of harm to an inmate's

health," regardless of social attitudes and

legislative responses to that practice. The

court suggested an appropriate basis for

comparison: "whether the type of exposure

potentially faced by a nonsmoking prisoner

double-celled with a smoker constitutes a

health hazard at least as significant as denial

of exercise," which has been found to violate

the Eighth Amendment in numerous decisions

(including LeMaire, discussed above).

The Clemmons case has been accepted for

rehearing en banc by the full ten-judge

appellate court.

Crowding/Remedies/

Pre-trial Detainees

Arecent decision from the Supreme Judicial

Court of Massachusetts in a jail crowding case

demonstrates that court's willingness to apply

federal constitutional guarantees in a manner

similar to the federal courts.

In Richardson v. Sheriff ofMiddlesex

County, 407 Mass. 455, 553 N.E.2d 1286 (Mass.

1990), the court upheld the trial court's

conclusion that crowding in the Middlesex

County jail constituted unlawful punishment

of pre-trial detainees. In a familiar scenario,

the jail-a modern structure constructed with

a capacity of 161-had at times held as many

as 303 inmates, and the overflow was housed

in visiting rooms, common areas, dayrooms,

and other makeshift housing areas.

The appeals court agreed that it is unconstitutional to require inmates to sleep on the

floor, with or without mattresses, or to hold

them in makeshift dormitories without access

to toilets and showers or with inadequate

toilet and shower facilities. (The trial judge

had cited some areas with only two toilets and

one shower for sixty prisoners.) The court also

agreed that crowding inmates into common

areas-particularly those designed as open or

recreational space for inmates-was unconstiWINTER 1991

7

tutional, as was double bunking in holding

cellsthat were not only small but contained

benches that further reduced the floor area.

Although the trial court had relied in large

part on state regulations, the appeals court

preferred to focus on the inmates' constitutional claims, relying almost entirely on

precedent from the federal courts. But it

concluded that the state regulations were

entitled to "some weight" in assessing the

standards of decency against which constitutional claims are measured.

The court rejected the sheriff's argument

that the jail's crowded conditions were

justified by a legitimate governmental

purpose, "to keep the facility operating so as to

detain unbailworthy defendants awaiting

tria!." 553 N.E.2d at 1293. It echoed the

sentiment of a federal court that

[tjhe only conceivablepurpose overcrowding...serves is to further the state's interest

in housing moreprisoners without creating

moreprison space. This basically economic

motive cannot lawfully excuse the imposition

on thepresumptively innocent[pretrial

detainees]ofgenuineprivations and hardship

over any substantialperiod of time....

553 N.E.2d at 1293, quoting LaReau v.

Manson, 651 F.2d 96, 104 (2nd Cir. 1981).

For these reasons the court affirmed the

trial judge's imposition of a population cap, as

well as his orders to comply with state

regulations with regard to bathroom facilities.

But it displayed the same reluctance as have

federal courts to intervene directly and

forcefully in criminal court practices and the

same concern for protocol if such intervention

becomes necessary. Thus, it rejected the

plaintiffs' request to direct special court

sessions for purposes of bail review, without

excluding the possibility that such an order

might ultimately be appropriate-but only

after the trial judge "request[ed]" the relevant

administrative justice to institute special

sessions and if necessary "sought" the

assistance of the Chief Administrative Justice

of the Trial Court.

informed consentdoctrine has becomefirmly

entrenched in American tort law....

The logical corollary ofthe doctrine of

informed consent is that the patientgnerally

possesses the right not to consen~ that is, to

refuse treatment. "

At 241: "The principle that a competent

Religion

". person has a constitutionally protected liberty

EmploymentDivision v. Smith, 494 u.s. --' ...,. interest in refusing unwanted medical treat110 S.Ct.1595, 108 L.Ed.2d 876 (1990). At 886:

. " ment may be inferred from our prior decis"...[T]he right of free exercise does not relieve.: .

ions." At n.7: The right is better analyzed as a

an individual of the obligation to comply an4;11

Fourteenth Amendment liberty interest than

as part of a "generalized constitutional right of

'valid and neutral law of general applicability

on the ground that the law proscribes (or

privacy." The Court\ssumes that the Conprescribes) conduct that his religion prescribes

stitution would gr,ant a competent person "a

(or proscribes).'" (Citations omitted.)

constitutionally protected right to refuse lifeOne court has already suggested that this

saving hydration and nutrition" (242), but holds

non-prison decision has "cut back, possibly to

that states may require proof by clear and conminute dimensions, the doctrine that requires

vincing evidence that the incompetent person

government to accommodate, at some cost,

would have wished to exercise that right.

minority religious preferences: the doctrine on

which all the prison religion cases are

founded." Hunafa v. Murphy, 907 F.2d 46, 48

U.S. COURT OF APPEALS

(7th Cir.1990).

achieve the desired result. Only if such

sanctions failed to work should contempt

sanctions against local legislators have been

considered. The court relies on the same

considerations that underlie legislative

immunity in reaching this conclusion.

Mental Health Care

Remedies/State-Federal Comity

U.S. SUPREME COURT

Missouri v.]enkins, 495 u.s. --' 110 S.Ct.

1651,109 L.Ed.2d 31 (1990). The imposition of a

tax increase by the district court to fund a desegregation remedy was an abuse of discretion.

It should have ordered the school district to

levy the tax and enjoined the operation of

contrary state laws. At 54: "The difference

between the two approaches is far more than

a matter of form. Authorizing and directing

local govern-ment institutions to devise and

implement remedies not only protects the

function of the institutions but, to the extent

possible, also places the responsibility for

solutions to the problems of segregation upon

those who have themselves created the

problems."

The requirements of a tax increase in the

aid of ending constitutional violations did not

exceed the court's equitable powers or Article

III jurisdiction and did not violate the

Eleventh Amendment. At 58: "Even though a

particular remedy may not be required in

every case to vindicate constitutional

guarantees, where (as here) it has been found

that a particular remedy is required, the State

cannot hinder the process by preventing a

local government from implementing that

remedy." The opposite result would be

contrary to the Supremacy Clause.

Contempt

Medical Care/Theories-Due Process

Other Cases

Worth Noting

Spallone v. United States, 493 u.s. --' 110

S.Ct. 625, 107 L.Ed.2d 644 (1990). It was an

abuse of discretion to impose contempt

sanctions directly on Yonkers City Council

members for failing to vote for desegregation

relief when there was a reasonable probability that sanctions against the city itself would

8 WINTER 1991

Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Dept. ofHealth,

497 u.S. --' 110 S.Ct. 2841, 111 L.Ed.2d 224

(1990). At 111 L.Ed.2d 236:

"This[common law] notion of bodily

integrity has been embodied in the requirement that informed consent is generally

reqUiredfor medical treatment.... The

Thomas S. byBrooks v. Flaherty, 902 F.2d 250

(4th Cir.1990). In a class action dealing with

the mentally retarded in psychiatric hospitals,

the district court properly applied the Youngberg v. Romeo standard by declining to weigh

the decisions of treating professionals against

the testimony of plaintiffs' experts to decide

which of several acceptable standards to apply.

Rather, it found that many of the treating

professionals' decisions had not been implemented. It also found that many of their decisions departed from accepted standards of

treatment, based on the Secretary's written

standards and the plaintiffs' and defendants'

expert testimony concerning drug use, restraint,

and habilitation.

At 253: "Relevant accreditation is prima

facie evidence of constitutionally adequate

conditions." However, evidence of deficiencies

found by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals and by a federal agency

rebutted this presumption even though JCAH

had accredited the institution.

Attorneys' Fees and Costs

Plyler v. Evatt, 902 F.2d 273 (4th Cir.1990).

The court upholds fee awards at South

Carolina rates for attorneys from the National

Prison Project. Where plaintiffs prevailed in

the underlying litigation but lost a motion to

modify and permit double-celling, they were

entitled to fees for defending the modification

motion, since it was "intertwined with the

original claims" and counsel were under "clear

obligation to make the defensive effort." (281)

Procedural Due Process

Meador v. Cabinetfor Human Resources, 902

F.2d 474 (6th Cir.1990). Astate statute proTHE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

viding that "[t]he cabinet shall arrange for a

program of care, treatment and rehabilitation

of the children committed to it," and that "the

cabinet shall be responsible for the operation,

management and development of the existing

state facilities for the custodial care and rehabilitation of children," created an "entitlement to protective services" protected by due

process. The plaintiffs' allegation was that

they had been sexually abused in a foster

home (apparently an institution).

Procedural Due ProcessDisciplinary Proceedings/Discovery

Wagner v. Henman, 902 F.2d 578 (7th Cir.

1990). The plaintiff was convicted of murder

in a prison disciplinary proceeding. The

district court erred in requiring total

disclosure of an FBI report to plaintiff's

counsel without considering the risk of

inadvertent disclosure of information that

might identify confidential informants and

without looking for ways in which such risk

could be avoided, such as redacting the

documents.

Publications/Qualified Immunity

Allen v. Higgins, 902 F.2d 682 (8th Cir.1990).

The plaintiff was denied the right to receive a

government surplus catalog and a jury

awarded him $1.00. The responsible prison

official made this decision without examining

the catalog, which was shown at trial not to

pose a security threat. He was not entitled to

qualified immunity since, without examining

the catalog, he could not have reasonably

assessed whether his conduct violated clearly

established law, and its exclusion did not

serve legitimate penological interests.

False Imprisonment

Lee v. Dugger, 902 F.2d 822 (11th Cir.1990).

The plaintiff was held for an extra year

because prison officials refused to give him

the benefit of an intermediate state appellate

court decision regarding the proper calculation of "gain time." Instead, they argued in his

state habeas pr~ceeding in the same court that

the earlier decision was wrong. One judge held

that defendants were entitled to qualified

immunity because one case, decided by an

intermediate appellate court, "falls short of

the clarity of the law required to defeat a

defense of qualified immunity," and defendants were "entitled to attempt to persuade the

same court that its prior decision was in error."

Asecond judge, concurring specially, argued

that the plaintiff's rights were not violated

because he received the process due through

his state court habeas petition. Judge Johnson,

dissenting, argues that the statutes created a

liberty interest, the first court decision clearly

established the law, and pre-deprivation

process was required.

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

Mental Health Care

Societyfor Good Will to Retarded Children

v. Cuomo, 902 F.2d 1085 (2d Cir.1990).Judge

Weinstein's latest findings of unconstitutionality in this case do not meet Rule 52's

requirement that facts be found "specially."

Findings of unconstitutionality from

proceedings made seven years earlier cannot

be relied on to support the present findings

because the district court acknowledged that:~

there had been "enormous improvements.",.,'

A"sweeping grant of relief" could not be .'~j:;

justified absent any specific findings that/~

patients had regressed as a result of present

conditions,'

The district court also departed from the

Youngberg v. Romeo standard by failing to

determine whether treatment and conditions

actually departed from accepted professional

judgment. "The court instead misused expert

testimony by treating it as evidence of

alternative choices against which the

institution's treatment should be compared."

(1089) Experts are to be used only to help the

court determine what the minimum professional standard is.

Relief requiring population reduction and

community placement was not narrowly

tailored. The court should not have granted

injunctive relief "without first identifying the

specific constitutional violations that each

part of the ordered remedy would cure."

(1090) The conclusory statement that

"administrative limitations" made it impossible to remedy the violations without

reducing population was insufficient;

defendants should have a chance to cure the

"administrative limitations." Court-ordered

community placement is a remedy of last

resort.

Use of Force/Medical CareStandards of Liability

Simpson v. Hines, 903 F.2d 400 (5th Cir.

1990). The decedent was arrested and put in a

celL He brandished marijuana, and refused to

give it or his other property up. Ten officers

came into the celL Simpson wound up

handcuffed and dead from asphyxia caused

by neck trauma.

The court treats this as a case arising

"before or during arrest" and therefore

governed by the Fourth Amendment, without

any discussion of where arrest ends and

detention begins.

Afactual issue precluding summary

judgment was created by the presence of ten

officers, the use of a neckhold, an officer's

sitting "astraddle" the plaintiff (i.e., on his

chest), the nature of the injury, and a tape

recording of the decedent's screams and cries

for mercy along with "statements from which

the trier-of-fact might infer malice."

Evidence that the decedent was uncon-

scious when the officers left the cell and that

they knew he had heavily exerted himself

during the struggle and was under the influence of drugs, combined with the officers'

callous statements on the tape, supported an

inference of deliberate indifference, as did the

failure of another officer, who later observed

that the decedent was not moving, to summon

medical help.

Pre-trial detainees are owed a duty of "reasonable medical care unless the failure to supply that care is reasonably related to a legitimate governmental objective." (404) The court

does not explain 'tow this standard differs from

the deliberate inA'ifference standard.

.'"

Pre-Trial Detainees/Suicide

Prevention/Municipalities/Training

Burns v. City Of Galveston, Texas, 905 F.2d 100

(5th Cir.1990). Here is yet another case of a

drunken arrestee who behaved bizarrely and

then killed himself. There was evidence that he

had threatened to kill himself if he didn't get a

cigarette, but the officers testified that because

of other noise in the jail they didn't understand

what he was yelling. Another prisoner called

out to the officers when he saw the decedent

hanging, and they told him to be quiet.

An alleged failure to make hourly cell checks

required by city policy could not establish

municipal liability because the decedent killed

himself less than an hour after admission.

The failure fully to implement psychological

screening procedures contained in a.municipal

manual did not support municipal liability

because there is no "absolute right to psychological screening." (104) Officers need not be

trained to screen for suicidal tendencies; this

"requires the skills of an experienced medical

professional with psychiatric training."

Religion-PracticesBeards, Hair, Dress

Benjamin v. Coughlin, 905 F.2d 571 (2d Cir.

1990). Equal protection claims based on

disparate treatment of religious groups are

evaluated by a reasonableness standard similar

to the Turner/Shabazz standard.

Defendants in this class action were precluded from contesting the unconstitutionality

of requiring intake haircuts for Rastafarian

inmates by decisions of the state court of

appeals even though they were rendered in

individual actions, since there was a "substantial overlap" of evidence and argument and

defendants had both incentive and opportunity

to contest the issue. The haircut requirement

was unconstitutional because there was a

nearly costless alternative, tying the hair in

pony tails for an intake photograph.

Protection from Harm

Fruit v. Norris, 905 F.2d 1147 (8th Cir.1990).

The plaintiffs were disciplined for refusing to

WINTER 1991

9

clean out a raw sewage facility without the

protective clothing and equipment called for

by the operations manual. The temperature

was 125 degrees. The district court dismissed

because there was no evidence that the

defendants had actual or constructive

knowledge of serious dangers.

Intentionally placing inmates in dangerous

surroundings violates the Eighth Amendment.

The plaintiffs made out a prima facie case

because common sense suggests that defendants should have known the dangers of

heatstroke and of disease spread through

contact with human waste.

Women/Good Time/Equal Protection

Jackson v. Thornburgh, 907 F.2d 194 (D.C.Cir.

1990). Astatute that grants early release to

prisoners in District of Columbia prisons does

not deny equal protection to D.C. women

offenders who are housed in federal prisons

and do not receive the statute's benefits.

Heightened scrutiny is not applicable because

the distinction is not based on gender but on

place of incarceration, "although its interaction with the District's gender-specific

prisoner-assignment rules clearly make it

disadvantageous to be female." The disadvantaged class does include males, and some

women (those with short sentences) do

benefit from the statute. There is a rational

basis for the distinction in the fact that the

District of Columbia is under a constitutional

obligation to reduce crowding in its prisons.

Protection from Inmate Assault

Wrightv.Jones, 907 F.2d 848 (8th Cir.1990).

The plaintiff was assaulted by other inmates

and beaten for five minutes before guards

intervened. This assault followed a period in

which large numbers of inmates had

congregated in the housing unit and there

were numerous fights. Evidence that the

guards had knowledge of the prior assaults,

had a duty to supervise the housing area, and

had a clear view of the area created a jury

issue under the reckless disregard standard.

The Whitley standard

of "malicious and

...

sadistic" behavior does not apply "because the

guards have not identified a competing

obligation which inhibited their efforts to

protect inmates." (851) The phrase "highly

foreseeable" found in the instructions to the

jury does not impose a standard of mere or

gross negligence; viewed in context, it required

that defendants have had notice of the

danger. "Under our precedents, liability can be

imposed if guards disregard a known risk to

the safety of inmates." (851)

Modification ofJudgments/Administrative Segregation-Death Row

McDonald v. Armontrout, 908 F.2d 388 (8th

Cir.1990). Aclass action challenging death

10 WINTER 1991

row conditions was resolved by a consent

decree. Two years later, defendants sought to

move the unit to a newly built prison and

asked for other modifications consistent with

their implementation plan. Plaintiffs objected

to the reduction of outdoor exercise time from

16 hours to four hours a week; a smaller and

less well equipped yard; greater restrictions on ;;:

religious services; and limited non-legal

'J'

telephone access (one hour a week). These

restrictions were imposed on the highersecurity death row prisoners; those in less

restrictive classifications received more

recreation time and other benefits.

The modifications were properly approved.

The move to a new prison was explicitly contemplated in the original judgment and the

court would have had power to approve it in

any case.

Handicapped/Jury Instructions/State,

Local and Professional Standards

Evans v. Dugger, 908 F.2d 801 (11th Cir.1990).

The partly paraplegic plaintiff was denied

appropriately designed toilet and shower areas

and adequate access to toilet and shower, and

denied adequate exercise and physical therapy.

Denial of adequate care to a disabled

prisoner is to be judged under the Estelle

deliberate indifference standard and not the

Whitley standard, since there was no clash

between treating him and meeting other

legitimate needs.

The district court properly instructed the

jury that compliance with "generally accepted

standards requiring handicapped accessibility"

is not legally required in prison housing, but

such standards may be considered insofar as

they are relevant. The plaintiff had requested

an instruction that noncompliance with the

state statute was evidence of deliberate

indifference and a basis for holding particular

noncomplying officials liable.

Suicide Prevention/Municipalities/

State, Local and Professional

Standards

Popham v. City of Talladega, 908 F.2d 1561

(lIth Cir.1990), aff'g742 F.Supp.1504 (N.D.Ala.

1989). The plaintiff was arrested for public

intoxication. He was emotional, depressed, and

angry. His belt and shoes were taken and his

cell was ordered monitored by TV. After 11:00

p.m., there was no physical monitoring

because there were no guards on duty. The

plaintiff hanged himself with his blue jeans in

a space in the cell out of view of the camera.

Jail suicide cases are governed by a

deliberate indifference standard and the

determination turns on "the level of knowledge possessed by the officials involved, or

that which should have been known as to an

inmate's suicidal tendencies." (1564) "Absent

knowledge of a detainee's suicidal tendencies,

the cases have consistently held that failure to

prevent suicide has never been held to

constitute deliberate indifference." (1564) The

decedent had been jailed before and had not

threatened suicide. The defendants didn't

know that he had tried to commit suicide two

days previously. They didn't know that he was

threatening suicide from his jail cell. The

removal of shoelaces, belts, etc., and the

presence of closed circuit cell monitoring

show the absence of deliberate indifference.

Protection from Inmate Assault/

Statutes of Lim\tations/Qualified

Immunity ..•J

Ayala SerranotiJ." Lebron Gonzales, 909 F.2d

8 (1st Cir.1990). The plaintiff was assaulted by

other inmates and stabbed repeatedly in view

of the defendant officer, who did nothing. A

court awarded him $20,000.

The plaintiff's amended complaint, filed by

counsel, related back for limitations purposes

to the time of filing of the pro se complaint,

which named the defendant's supervisors.

The defendant was not entitled to qualified

immunity where he neither intervened in the

assault nor summoned others to help.

Pre-Trial Detainees/Use of Force/

Medical Care-Denial of Ordered Care

Martin v. Board of County Commissioners

ofPueblo County, 909 F.2d 402 (10th Cir.1990).

The plaintiff was arrested while in the

hospital recovering from a neck fracture and

was moved against doctor's orders.

Pre-trial detainees are entitled to the benefit of the same deliberate indifference standard applied to convicts' medical care. The reasonableness of an arrest involving movement

of an injured person is governed by the same

standard. Physical contact is not necessary to a

Fourth Amendment use of force claim; the

threat of physical coercion may be sufficient.

Defendants were not entitled to qualified

immunity. At 407: "The absence of authority on

all fours with the unusual facts of this case

should not be considered fatal to plaintiff's

claim, in light of the patently insubstantial

character of the distinction upon which defendants' qualified immunity argument rests."

Access to Courts-Punishment and

Retaliation/Work Assignments

Madewell v. Roberts, 909 F.2d 1203 (8th Cir.

1990). Medically disabled inmates were assigned to "inside utility" work (vegetable processing) and made to work at night sitting directly

on a concrete floor. They were excluded from

"Class I" status, a classification which permitted inmates to earn more good time.

Allegations that prison officials retaliated

for plaintiffs' lawsuit by blocking reclassification opportunities and worsening their living

and working conditions raised a factual issue

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

n

that should not have been decided against

plaintiffs on summary judgment. The manifestations of retaliation need not themselves amount

to constitutional violations. "The violation lies in

the intent to impede access to the courts." (1207)

The plaintiff's allegation that his serious

arthritis was painfully aggravated by sitting

on cold concrete for hours in an unheated

space could support the conclusion that his

work assignment was dangerous to health or

unduly painfuL

Psychotropic Medication/

Qualified Immunity

Bee v. Greaves, 910 F.2d 686 (10th Cir.1990).

The plaintiff received a jury verdict of $100

actual and $300 punitive damages for the

forcible administration of thorazine. The doctor was not entitled to qualified immunity.

The Supreme Court in Washington v. Harper

said it had "no doubt" that the plaintiff had a

liberty interest in avoiding unwanted medication, citing Vitek and Parham v.JR., which

pre-dated the plaintiff's involuntary medication.

Administrative SegregationHigh Security/Cruel and Unusual

Punishment

McCord v. Maggio, 910 F.2d 1248 (5th Cir.

1990). The plaintiff alleged that he was

confined for 23 hours a day in "Closed-Cell

Restriction" in "an unlighted, windowless cell

with only a hole cut in the steel door for

outside access, while water and human waste

sometimes up to ankle high seeped into the

cell from frequently broken fixtures and

pipes," and of being required to sleep on a

mattress on the floor under these conditions.

The magistrate should have made findings of

fact as to the plaintiff's living conditions and

assessed the totality of conditions, despite the

defendants' argument that the facilities "were

old and worn down, but prison officials did

the best that they could given the conditions."

(1250) The State Health and Safety Code is a

"valuable index" of contemporary levels of

decency but is not the only stanl!ard by which

they are judge<\.."Conditions not condemned as

unfit for human habitation in the prison

setting have been held to still amount to a

violation of a prisoner's Eighth Amendment

rights." (1250)

Religion-Practices-Names

Ali v. Dixon, 912 F.2d 86 (4th Cir.1990).

Prison officials' refusal to add the newly

converted plaintiff's Muslim name to some of

his prison records, requiring him to use his old

name when drawing money from his account,

would violate his First Amendment rights in

the absence of any penological justification

for the refusaL The prison's refusal to add the

new name to official correspondence with the

plaintiff would also violate his rights unless

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEO JOURNAL

prison officials showed that there was a risk

of misfiling. Defendants' arguments were

addressed to substituting the new name in

their records (which they are not required to

do) rather than adding it.

The continued use of his old name by prison

staff in addressing him did not violate his

rights because of the importance of having

staff know prisoners by name and the interference of name changes with that familiaritfr.·

1990). The District of Columbia Good Time

Act, which limits eligibility for certain good

time credits to those convicted of D.C. criminal

offenses and incarcerated in D.C. prisons, did

not deny equal protection to D.C. offenders

housed in federal prisons because it was

rationally related both to the goal of relieving

crowding in D.C. and the goal of letting the

prison system with actual custody apply its

good time system.

-~_.~.

Service of Process

'::.

Puett v. Blandford, 912 F.2d 270 (9th Ci~}C

1990). At 275:

..

..'[WJe hold that an incarceratedpro se

plaintiffproceeding in forma pauperis is

entitled to rely on the u.s. Marshal for service

Of the summons and complaint and, having

prOVided the necessary information to help

effectuate service, plaintiffshould not be

penalized by having his or her action dismissedfor failure to effect service where the

u.s. Marshal or the court clerk hasfailed to

perform the duties required of them....

If mail serviceproves unsuccessfu4 the

Marshals should be directed to serve the

complaintpersonally.

Suicide

BUffington v. Baltimore County, Md., 913

F.2d 113 (4th Cir.1990). The court rejects

defendants' argument that under DeShaney,

jail officials are not required to take steps to

prevent the suicide of people who have been

civilly committed so they won't hurt

themselves. If the state has taken custody of

someone, its obligations do not depend on the